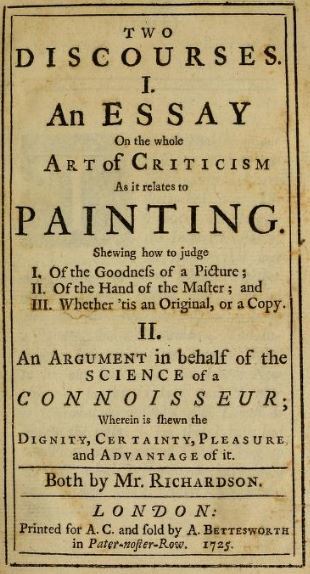

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, An Essay on the Theory of Painting. By Mr. Richardson. The Second Edition, Enlarg'd, and Corrected, London, A. C. - A. Bettesworth, 1725.

Son Essay on the Theory of Painting se caractérise par une volonté de promouvoir une école britannique de peinture, très souvent dénigrée en raison de sa pratique presque exclusive des genres picturaux dits bas, et notamment du portrait, mais aussi à cause de la présence d’un grand nombre d’artistes étrangers sur son sol. À travers son Essay, Richardson tente de prouver l’utilité de l’art, et, s’adressant aux artistes britanniques, de les convaincre d’étudier et d’atteindre le meilleur d’eux-mêmes, afin qu’une école anglaise de peinture soit reconnue. Cette volonté nationaliste est d’autant plus intéressante que Richardson écrit peu après la fusion des parlements anglais et écossais (1707) qui crée alors le « Royaume-Uni de Grande-Bretagne ». On note qu’à partir de 1711, Richardson fait partie de l’Académie de Great Queen Street, se caractérisant par une volonté de réunir des artistes et notamment des portraitistes, et de leur donner une certaine visibilité.

Par ailleurs, Richardson est à la recherche d’une certaine indépendance, ce qui est visible dans son refus de demander à un prince ou un aristocrate d’être à la tête de cette Académie. Un reflet de cette volonté apparaît dans l’absence de dédicataire de son Essay.

Comme le soulignent I. Baudino et F. Ogée, les écrits de Richardson « constituent le premier maillon d’un travail d’anglicisation du discours sur l’art […], qui offrait enfin aux artistes anglais et à leur public un langage et une méthode leur permettant d’affirmer une identité et une originalité nationales ». Le fait que Richardson utilise presque toujours des mots anglais lorsqu’il évoque des notions de théorie artistique semble indiquer ce souhait. En effet, Richardson se sert peu de mots français ou italiens, à l’exception de clair-obscur et tout-ensemble, ce dernier mot étant néanmoins traduit dans certains cas par whole together.

Même si Richardson peut s’inspirer des théoriciens français comme Roger de Piles, il développe néanmoins une vision différente. Il estime par exemple qu’il existe sept parties de la peinture (invention, expression, composition, dessin, coloris, maniement, grâce et grandeur) alors que Roger de Piles n’en distingue que trois (composition, dessin, coloris). Le chapitre sur le sublime, un peu remanié par rapport à la première édition, est également très développé, mais ne s’applique pas seulement à l’art (Richardson le commence en évoquant l’écriture).

Il est à noter qu’on ne retrouve aucune illustration insérée directement dans le texte, bien que de nombreux exemples d’œuvres soient donnés par Richardson (et en particulier les Cartons de Raphaël, qui étaient alors exposés à Hampton Court, lieu relativement accessible au public).

Élodie Cayuela

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, An Essay on the Theory of Painting, London, W. Bowyer, 1715.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, The Works of Mr. Jonathan Richardson. Consisting of I. The Theory of Painting. II. Essay on the Art of Criticism, so far as it relates to Painting. III. The Science of a Connoisseur. All corrected and prepared for the Press By his Son Mr. J. Richardson, RICHARDSON, Jonathan Junior (éd.), London, T. Davies, 1773.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, The Works of Jonathan Richardson. Containing I. The Theory of Painting. II. Essay on the Art of Criticism, (So far as it relates to Painting). III. The Science of a Connoisseur. A New Edition, corrected, with the Additions of An Essay on the Knowledge of Prints, and Cautions to Collectors, Ornamented with Portraits by Worlidge, &c. of the most Eminent Painters mentioned. Dedicated, by Permission, to Sir Joshua Reynolds, London, T. et J. Egerton, 1792.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, The Works, Hildesheim, G. Olms, 1969.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, Traité de la peinture et de la sculpture, trad. par RUTGERS, Antoine et TEN KATE, Lambert, Genève, Minkoff Reprint, 1972.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, Traité de la peinture et de la sculpture, BAUDINO, Isabelle et OGÉE, Frédéric (éd.), Paris, École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 2008.

SNELGROVE, Gordon William, The Work and Theories of Jonathan Richardson (1665-1745), Thesis, University of London, 1936.

PAKNADEL, Félix, Critique et peinture en Angleterre de 1660 à 1770, Thèse de doctorat, Université de Provence, 1978.

HABERLAND, Irene, Jonathan Richardson, 1666-1745 : die Begründung der Kunstkennerschaft, Münster, LIT, 1991.

GIBSON-WOOD, Carol, Jonathan Richardson: Art Theorist of the English Enlightenment, New Haven - London, Yale University Press, 2000.

GIBSON-WOOD, Carol, « “A Judiciously Disposed Collection”: Jonathan Richardson Senior's Cabinet of Drawings », dans BAKER, Christopher, ELAM, Caroline et WARWICK, Genevieve (éd.), Collecting Prints and Drawings in Europe (c. 1500-1750), Aldershot, Ashgate, 2003, p. 155-171.

GEEST, Simone von der, The Reasoning Eye: Jonathan Richardson's (1667-1745) Portrait Theory and Practice in the Context of the English Enlightenment, Thesis, University of London, 2005.

HAMLETT, Lydia et BONETT, Helena, « Sublime Portraiture: Jonathan Richardson’s Portrait of the Artist’s Son, "Jonathan Richardson Junior, in his Study" and Anthony Van Dyck’s "Portrait of Lary Hill, Lady Killigrew" », dans LLEWELLYN, Nigel et RIDING, Christine (éd.), The Art of the Sublime, 2013 [En ligne : https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/the-sublime/lydia-hamlett-and-helena-bonett-sublime-portraiture-jonathan-richardsons-portrait-of-the-r1138671 consulté le 09/05/2016].

FILTERS

QUOTATIONS

The great Business of Painting I have often said, and would fain inculcate, is to relate a History, or a Fable, as the best Historians, or Poets have done ; to make a Portrait so as to do Justice at least, and Sometimes not without a little Complaisance ; and that to the Mind, as well as to the Face, and Person ; To represent Nature, or rather the Best of Nature ; and where it can be done, to Raise and Improve it ; to give all the Grace and Dignity the Subject has, all that a well instructed Eye can discover in it, or which such a Judgment can find ‘tis Capable of in its most Advantagious Moments.

Contrairement aux autres passages de l'Essay on the Theory of Painting, la préface n'est pas traduite dans l'édition française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Neatness, and high Finishing ; a Light, Bold Pencil ; Gay, and Vivid Colours, Warm, and Sombrous ; Force, and Tenderness, All these are Excellencies when judiciously employ’d, and in Subserviency to the Principal End of the Art ; But they are Beauties of an Inferior Kind even when So employ’d ; they are the Mechanick Parts of Painting, and require no more Genius, or Capacity, than is necessary to, and frequently seen in Ordinary Workmen ; […] ; These properties are in Painting, as Language, Rhime, and Numbers are in Poetry ; and as he that stops at These as at what Constitutes the Goodness of a Poem is a Bad Critick, He is an Ill Connoisseur who has the same Consideration for these Inferious Excellencies in a Picture.

How much more if for the sake of These, a Picture is esteemed where the Story is Ill Told, and Nature is Ill represented, or not well chosen : If it be imagin’d to be good, because a Piece of Lace, or Brocade, a Fly, a Flower, a Wrinkle, a Wart, is highly finish’d, and (if you please) Natural, and well in its Kind ; or because the Colours are Vivid, or the Lights and Shadows Strong, though the Essential Parts are without Grace or Dignity, or are even Ridiculous.

Contrairement aux autres passages de l'Essay on the Theory of Painting, la préface n'est pas traduite dans l'édition française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Neatness, and high Finishing ; a Light, Bold Pencil ; Gay, and Vivid Colours, Warm, and Sombrous ; Force, and Tenderness, All these are Excellencies when judiciously employ’d, and in Subserviency to the Principal End of the Art ; But they are Beauties of an Inferior Kind even when So employ’d ; they are the Mechanick Parts of Painting, and require no more Genius, or Capacity, than is necessary to, and frequently seen in Ordinary Workmen ; […] ; These properties are in Painting, as Language, Rhime, and Numbers are in Poetry ; and as he that stops at These as at what Constitutes the Goodness of a Poem is a Bad Critick, He is an Ill Connoisseur who has the same Consideration for these Inferious Excellencies in a Picture.

Contrairement aux autres passages de l'Essay on the Theory of Painting, la préface n'est pas traduite dans l'édition française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Contrairement aux autres passages de l'Essay on the Theory of Painting, la préface n'est pas traduite dans l'édition française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Contrairement aux autres passages de l'Essay on the Theory of Painting, la préface n'est pas traduite dans l'édition française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Contrairement aux autres passages de l'Essay on the Theory of Painting, la préface n'est pas traduite dans l'édition française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Contrairement aux autres passages de l'Essay on the Theory of Painting, la préface n'est pas traduite dans l'édition française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Contrairement aux autres passages de l'Essay on the Theory of Painting, la préface n'est pas traduite dans l'édition française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Contrairement aux autres passages de l'Essay on the Theory of Painting, la préface n'est pas traduite dans l'édition française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Contrairement aux autres passages de l'Essay on the Theory of Painting, la préface n'est pas traduite dans l'édition française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Contrairement aux autres passages de l'Essay on the Theory of Painting, la préface n'est pas traduite dans l'édition française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Painting is that Pleasant, Innocent Amusement. But ’tis More ; ’tis of great Use, as being one of the means whereby we convey our Ideas to each other, and which in some respects has the Advantage of all the rest. And thus it must be rank’d with These, and accordingly esteem’d not only as an Enjoyment, but as another Language, which completes the whole Art of communicating our Thoughts ; one of those particulars which raises the Dignity of Human Nature so much above the Brutes ; and which is the more considerable, as being a Gift bestowed but upon a Few even of our own Species.

Words paint to the Imagination, but every Man forms the thing to himself in his Own way : Language is very Imperfect : There are innumerable Colours, and Figures for which we have no name, […] ; whereas the Painter can convey his Ideas of these Things Clearly, and without Ambiguity ; and what he says every one understands in the Sense he intends it.

And this is a Language that is Universal ; Men of all Nations hear the Poet, Moralist, Historian, Divine, or whatever other Character the Painter assumes, speaking to them in their own Mother Tongue.

The Pleasure that Painting, as a Dumb Art, gives us, is like what we have from Musick ; its beautiful Forms, Colours and Harmony, are to the Eye what Sounds, and the Harmony of that kind are to the Ear ; and in both we are delighted in observing the Skill of the Artist in proportion to It, and our own Judgment to discover it.

Conceptual field(s)

By the help of this Art [ndr : la peinture] we have the Pleasure of seeing a vast Variety of Things and Actions, of travelling by Land or Water, of knowing the Humours of Low Life without mixing with it, of viewing Tempests, Battels, Inundations ; and, in short, of all Real or Imagin’d Appearances in Heaven, Earth, or Hell ;

Nor do we barely see this Variety of Natural Objects, but in Good Pictures we always see Nature Improv’d, or at least the best Choice of it. We thus have nobler and finer Ideas of Men, Animals, Landscapes, &c. than we should perhaps have ever had ;

And if moreover what I write may hereafter happen to be of use of any body else, whether it be to put a Lover of Art in a Method to judge of a Picture, (and which in most things a Gentleman may do altogether as well as a Painter) or to awaken some useful Hints in some of my own Profession ; […] If these Consequences happen, it will be a Satisfaction to me over and above.

So by conversing with the Works of the best Masters in Painting, one forms better Images whilst we are Reading, or Thinking. I see the Divine Airs of Rafaëlle when I read any History of our Saviour, or the Blessed Virgin ; and the Awful ones he gives an Apostle when I read of their Actions, and conceive of those Actions that He, and Other great Men describe in a Nobler manner than otherwise I should ever have done.

To come to Portraits ; the Picture of an absent Relation, or Friend, helps to keep up those Sentiments which frequently languish by Absence and may be instrumental to maintain, and sometimes to augment Friendship, and Paternal, Filial, and Conjugal Love, and Duty.

Upon the sight of a Portrait, the Character, and Master-strokes of the History of the Person it represents are apt to flow in upon the Mind, and to be the Subject of Conversation : So that to sit for one’s Picture, is to have an Abstract of one’s Life written, and published, and ourselves thus consign’d over to Honour, or Infamy.

But (by the way) ‘tis not every Picture-maker that ought to be called a Painter, as every Rhymer, or Grubstreet Tale-Writer is not a Poet, or Historian : a Painter ought to be a Title of Dignity, and understood to imply a Person endued with such Excellencies of Mind, and Body, as have ever been the Foundations of Honour amongst Men.

He that Paints a History well, must be able to Write it ; he must be throughly inform’d of all things relating to it, and conceive it clearly, and nobly in his Mind, or he can never express it upon the Canvas : He must have a solid Judgment, with a lively Imagination, and know what Figures, and what Incidents ought to be brought in, and what every one should Say, and Think.

and Painting, as well as Poetry, requiring an Elevation of Genius beyond what pure Historical Narration does ; the Painter must imagine his Figures to Think, Speak, and Act, as a Poet should do in a Tragedy, or Epick Poem ; especially if his Subject be a Fable, or an Allegory. If a Poet has moreover the Care of the Diction, and Versification, the Painter has a Task perhaps at least Equivalent to That, after he has well conceived the thing (over and above what is merely Mechanical, and other particulars, which shall be spoken to presently) and that is the Knowledge of the Nature, and Effects of Colours, Lights, Shadows, Reflections, &c.

Il est intéressant de noter que le traducteur a choisi de traduire l'expression "Elevation of Genius" par le terme français "Relevé".

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

To be a good Face-Painter, a degree of the Historical, and Poetical Genius is requisite, and a great Measure of the other Talents, and Advantages which a good History-Painter must possess : Nay some of them, particularly Colouring, he ought to have in greater Perfection than is absolutely necessary for a History-Painter.

‘Tis not enough to make a Tame, Insipid Resemblance of the Features, so that every body shall know who the Picture was intended for, nor even to make the Picture what is often said to be prodigious Like : (This is often done by the lowest of Face-Painters, but then ‘tis ever with the Air of a Fool, and an Unbred Person ;) A Portrait-Painter must understand Mankind, and enter into their Characters, and express their Minds as well as their Faces : And as his Business is chiefly with People of Condition, he must Think as a Gentleman, and a Man of Sense, or ‘twill be impossible to give Such their True, and Proper Resemblances.

But if a Painter of this kind is not oblig’d to take in such a compass of Knowledge as he that paints History, and that the Latter upon Some accounts is the nobler Employment, upon Others the Preference is due to Face-Painting ;

L'expression Face Painting n'apparait pas dans la traduction française de 1728.

Conceptual field(s)

Le terme Portrait-Painter n'est pas directement traduit dans la version française de 1728, le traducteur ayant utlisé une forme impersonnelle. Il semble ne pas faire de différence en français entre "Face-Painter" et "Portrait-Painter", à la différence de l'anglais où les deux expressions sont employées en même temps.

Conceptual field(s)

To be a good Face-Painter, a degree of the Historical, and Poetical Genius is requisite, and a great Measure of the other Talents, and Advantages which a good History-Painter must possess : Nay some of them, particularly Colouring, he ought to have in greater Perfection than is absolutely necessary for a History-Painter.

‘Tis not enough to make a Tame, Insipid Resemblance of the Features, so that every body shall know who the Picture was intended for, nor even to make the Picture what is often said to be prodigious Like : (This is often done by the lowest of Face-Painters, but then ‘tis ever with the Air of a Fool, and an Unbred Person ;) A Portrait-Painter must understand Mankind, and enter into their Characters, and express their Minds as well as their Faces : And as his Business is chiefly with People of Condition, he must Think as a Gentleman, and a Man of Sense, or ‘twill be impossible to give Such their True, and Proper Resemblances.

Add to all this, that the Works of the Face-Painter must be seen in all the Periods of Beginnings, and Progress, as well as when Finish’d, when they are Not, oftner than when they Are fit to be seen, and yet Judg’d of, and Criticis’d upon, as if the Artist had given his last Hand to ‘em, and by all sorts of People ; nor is he always at liberty to follow his Own Judgment.

He [ndr : un peintre] must not only have a nice Judgment to distinguish betwixt things nearly Resembling one another, but not the same […], but he must moreover have the same Delicacy in his Eyes to judge of the Tincts of Colours which are of infinite Variety ;

He [ndr : un peintre] must not only have a nice Judgment to distinguish betwixt things nearly Resembling one another, but not the same […], but he must moreover have the same Delicacy in his Eyes to judge of the Tincts of Colours which are of infinite Variety ; and to distinguish whether a Line be streight, or curv’d a little ; whether This is exactly parallel to That, or oblique, and in what degree ; how This curv’d Line differs from That, if it differs at all, of which he must also judge ; whether what he has drawn is of the same Magnitude with what he pretends to imitate, and the like ;

He [ndr : un peintre] must not only have a nice Judgment to distinguish betwixt things nearly Resembling one another, but not the same […], but he must moreover have the same Delicacy in his Eyes to judge of the Tincts of Colours which are of infinite Variety ; and to distinguish whether a Line be streight, or curv’d a little ; whether This is exactly parallel to That, or oblique, and in what degree ; how This curv’d Line differs from That, if it differs at all, of which he must also judge ; whether what he has drawn is of the same Magnitude with what he pretends to imitate, and the like ; and must have a Hand exact enough to form these in his Work, answerable to the Ideas he has taken of them.

Conceptual field(s)

‘Twas never thought unworthy of a Gentleman to be Master of the Theory of Painting. On the contrary, if such a one has but a superficial Skill that way, he values himself upon it, and is the more esteem’d by others, as one who has attain’d an Excellency of Mind beyond those that are Ignorant in that particular.

‘Tis true, the Word Painter does not generally carry with it an Idea equal to what we have of other Professions, or Employments not Superior to it ; the Reason of which is, That Term is appropriated to all sorts of Pretenders to the Art, which being Numerous, and for the most part very Deficient, (as it must needs happen, so few having Abilities and Opportunities equal to such an Undertaking) These consequently have fallen into Contempt ; […] ; and this being visible in a great Majority, it has diminish’d the Idea which ought to be apply’d to the Term I am speaking of ; which therefore is a very Ambiguous one, and should be consider’d as such, if it be extended beyond This, that it denotes one practising such an Art, for no body can tell what he ought to conceive farther of the Man, whether to rank him amongst some of the Meanest, or equal to the most Considerable amongst Men.

THe whole Art of Painting consists of these Parts.

Invention, Expression, Composition, Drawing, Colouring, Handling, and Grace, and Greatness.

What is meant by these Terms, and that they are Qualities requisite to the Perfection of the Art, and really Distinct from each other, so that no one of ‘em can be fairly imply’d by any other, will appear when I treat of them in their Order ; and this will justify my giving so many Parts to Painting, which some others who have wrote on it have not done.

The Art in its whole Extent being too great to be compass’d by any one Man in any tolerable Degree of Perfection, some have apply’d themselves to paint One thing, and some Another : Thus there are Painters of Faces, History, Landscapes, Battels, Drolls, Still-Life, Flowers, and Fruit, Ships, &c. but every one of these several Kinds of Pictures ought to have all the several Parts, or Qualities just now mentioned [ndr : invention, expression, composition, drawing, colouring, handling, grace, greatness].

Conceptual field(s)

The History-Painter is obliged oftentimes to paint all these kinds of Subjects [ndr : visages, histoires, paysages, batailles, sujets grotesques, natures mortes, fleurs, fruits, bateaux, etc.], and the Face-Painter Most of ‘em ; but besides that they in such Cases are allow’d the Assistance of other Hands, the Inferior Subjects are in Comparison of their Figures as the Figures in a Landscape, there is no great Exactness required, or pretended to.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Italy has unquestionably produc’d the best Modern Painting, especially of the best Kinds, and posses’d it in a manner alone, when no other Nation in the World had it in any tolerable Degree ; That was Then consequently the great School of Painting. About a hundred Years ago there were a great many Excellent Painters in Flanders ; but when Van-Dyck came Hither, he brought Face-Painting to Us ; ever since which time (that is, for above fourscore Years) England has excell’d all the World in that great Branch of the Art, […] This may justly be esteem’d as a Complete, and the Best School for Face-Painting Now in the World ; and would probably have been yet Better, had Van Dyck’s Model been follow’d : But some Painters possibly finding themselves incapable of succeeding in His Way, and having found their Account in introducing a False Taste, Others have follow’d their Example, and forsaking the Study of Nature, have prostituted a Noble Art, chusing to exchange the honourable Character of good Painters for that sordid one of profess’d, mercenary Flatterers ;

but when Van-Dyck came Hither, he brought Face-Painting to Us ; ever since which time (that is, for above fourscore Years) England has excell’d all the World in that great Branch of the Art, […] This may justly be esteem’d as a Complete, and the Best School for Face-Painting Now in the World ; and would probably have been yet Better, had Van Dyck’s Model been follow’d : But some Painters possibly finding themselves incapable of succeeding in His Way, and having found their Account in introducing a False Taste, Others have follow’d their Example, and forsaking the Study of Nature, have prostituted a Noble Art, chusing to exchange the honourable Character of good Painters for that sordid one of profess’d, mercenary Flatterers ;

Conceptual field(s)

Of INVENTION

BEING determined as to the History that is to be painted, the first thing the Painter has do do, is To make himself Master of it as delivered by Historians, or otherwise ; and then to consider how to Improve it, keeping within the Bounds of Probability. Thus the Ancien Sculptors imitated Nature ; and thus the best Historians have related their Stories.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

The same Liberty of heightning a Story [ndr : que dans le carton de Raphaël représentant Jésus donnant les clés à saint Pierre] is very commonly taken in Pictures of the Crucifixion ; the Blessed Virgin is represented as Swooning away at the Sight, and S. John, and the Women with great propriety dividing their Concern between the two Objets of it, which makes a fine Scene, and a considerable Improvement ; and probably was the Truth, though the History says no such thing.

[…].

An Improvement much of the same Nature is the Angels that are frequently introduced in a Nativity, or on other Occasions, the noble, though not rich Habit of the Virgin, and the like, though perhaps not altogether in the same Degree of Probability.

La traduction du terme Improvement n'est pas littérale dans l'édition française de 1728. Le traducteur choisit en effet le terme Grâce, puis celui d'Invention. Dans le premier cas, l'insistance est mise sur la dimension esthétique, ce qui apparaît moins évident dans le texte anglais.

Conceptual field(s)

Under the present Rule is comprehended all those Incidents which the Painter invents to inrich his Composition ; and here in many Cases he has a vast Latitude, as in a Battel, a Plague, a Fire, the Slaughter of the Innocent, &c. Rafaëlle has finely imagined some of these (for example) in his Picture call’d the Incendio di Borgo. The Story is of a Fire at Rome miraculously extinguish’d by S. Leo IV. Because a Fire is seldom very great but when there happens to be a high Wind, he has painted such a one, as is seen by the flying of the Hair, Draperies, &c. There you see a great many Instances of Distress, and Paternal, and Filial Love.

Conceptual field(s)

A Painter is allow’d sometimes to depart even from Natural, and Historical Truth.

Thus in the Carton of the Draught of Fishes Rafaëlle has made a Boat too little to hold the Figures he has plac’d in it ; and this is so visible, that Some are apt to Triumph over that great Man, […] ; but the Truth is, had he made the Boat large enough for those Figures his Picture would have been all Boat, which would have had a Disagreeable Effect ; […].

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

But these Liberties [ndr : prises envers la vérité historique et naturelle] must be taken with great Caution and Judgment ; for in the main, Historical, and Natural Truth must be observed, the Story may be embellish’d, or something of it par’d away, but still So as it may be immediately known ; nor must any thing be contrary to Nature but upon great Necessity, and apparent Reason. History must not be corrupted, and turn’d into Fable or Romance : Every Person, and Thing must be made to sustain its proper Character ; and not only the Story, but the Circumstances must be observ’d, the Scene of Action, the Countrey, or Place, the Habits, Arms, Manners, Proportions, and the like, must correspond. This is call’d the observing the Costûme.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Every Historical Picture is a Representation of one single point of Time ; This then must be chosen ; and That in the Story which is the most Advantageous must be It. Suppose, for Instance, the Story to be painted is that of the Woman taken in Adultery, the Painter Seems to be at liberty to choose whether he will represent the Scribes and Pharisees accusing her to our Lord ; Or our Lord writing on the Ground ; Or pronouncing the last of the Words, Let him that is among you without Sin cast the first Stone at her ; Or lastly his Absolution, Go thy way, Sin no more.

Conceptual field(s)

Every Historical Picture is a Representation of one single point of Time ; This then must be chosen ; and That in the Story which is the most Advantageous must be It. Suppose, for Instance, the Story to be painted is that of the Woman taken in Adultery, the Painter Seems to be at liberty to choose whether he will represent the Scribes and Pharisees accusing her to our Lord ; Or our Lord writing on the Ground ; Or pronouncing the last of the Words, Let him that is among you without Sin cast the first Stone at her ; Or lastly his Absolution, Go thy way, Sin no more. […] When our Saviour says the Words, Let him that is without Sin cast the first Stone, He is the principal Actor, and with Dignity ; the Accusers are asham’d, Vex’d, Confounded, and perhaps Clamorous ; and the Accused in a fine Situation, Hope and Joy springing up after Shame, and Fear ; all which affords the Painter an opportunity of exerting himself, and giving a pleasing Variety to the Composition ; For besides the various Passions, and Sentiments naturally arising, the Accusers begin to disperse, which will occasion a fine Contrast in the Attitudes of the Figures, some being in Profile, some Fore-right, and some with their Backs turn’d ; some pressing forward as if they were attentive to what was said, and some going off : And this I should chuse ;

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Every Historical Picture is a Representation of one single point of Time ; This then must be chosen ; and That in the Story which is the most Advantageous must be It. Suppose, for Instance, the Story to be painted is that of the Woman taken in Adultery, the Painter Seems to be at liberty to choose whether he will represent the Scribes and Pharisees accusing her to our Lord ; Or our Lord writing on the Ground ; Or pronouncing the last of the Words, Let him that is among you without Sin cast the first Stone at her ; Or lastly his Absolution, Go thy way, Sin no more. […] When our Saviour says the Words, Let him that is without Sin cast the first Stone, He is the principal Actor, and with Dignity ; the Accusers are asham’d, Vex’d, Confounded, and perhaps Clamorous ; and the Accused in a fine Situation, Hope and Joy springing up after Shame, and Fear ; all which affords the Painter an opportunity of exerting himself, and giving a pleasing Variety to the Composition ; For besides the various Passions, and Sentiments naturally arising, the Accusers begin to disperse, which will occasion a fine Contrast in the Attitudes of the Figures, some being in Profile, some Fore-right, and some with their Backs turn’d ; some pressing forward as if they were attentive to what was said, and some going off : And this I should chuse ; for as to the Last, Tho’ there our Lord pronounces the decisive Sentence, and which is the principal Action, and of the most Dignity in the whole Story, yet Now there was no body left but himself, and the Woman ; the rest were all drop’d off one by one, and the Scene would be disfurnished.

Conceptual field(s)

There must be one Principal Action in a Picture. Whatever Under-Actions may be going on in the same instant with That, and which it may be proper to insert, to Illustrate, or Amplify the Composition, they must not divide the Picture, and the Attention of the Spectator.

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio) , La Mort d'Ananias, 1515 - 1516, gouache et huile sur carton, 340 x 530, London, Victoria & Albert Museum,

ROYAL LOANS.5.

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio) , La Transfiguration, 1516 - 1520, huile sur bois, 410 x 279, Vatican, Pinacoteca Vaticana, 40333.

Conceptual field(s)

Nor must the Attention be diverted from what ought to be Principal, by any thing how Excellent soever in it self. Protogenes in the famous Picture of Jalissus had painted a Partridge so exquisitely well, that it seem’d a Living Creature, it was admir’d by all Greece ; but That being most taken notice of, he defaced it entirely. That illustrious Action of Mutius Scævola’s putting his Hand in the Fire, after he had by Mistake kill’d another instead of Porsenna, is sufficient alone to employ his Mind ; Polydore therefore in a Capital Drawing I have of him of that Story, […] has left out the dead Man ; it was sufficiently known that one was kill’d, but that Figure, had it been inserted, would necessarily have diverted the Attention, and destroy’d that noble Simplicity, and Unity which now appears.

Every Action must be represented as done, not only as ‘tis possible it might be perform’d, but in the Best manner. In the Print after Rafaëlle, grav’d by Marc Antonio, you see Hercules gripe Anteus with all the Advantage one can wish to have over an Adversary : […]. Daniele da Volterra has not succeeded so well in his famous Picture of the Descent from the Cross, where one of the Assistants, who stands upon a Ladder drawing out a Nail, is so disposed as is not very Natural, and Convenient for the purpose.

DA VOLTERRA, Daniele (Daniele Ricciarelli), Descente de la croix, v. 1545, fresque, 337 x 221, Roma, Chiesa della Trinità dei Monti.

NATOIRE, Charles-Joseph, L'union de la Peinture et du Dessin, v. 1746, huile sur toile, Pas d'informations, Collection particulière.

CARRACCI, Annibale

DA VOLTERRA, Daniele (Daniele Ricciarelli)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

RAIMONDI, Marcantonio

Conceptual field(s)

DA VOLTERRA, Daniele (Daniele Ricciarelli), Descente de la croix, v. 1545, fresque, 337 x 221, Roma, Chiesa della Trinità dei Monti.

NATOIRE, Charles-Joseph, L'union de la Peinture et du Dessin, v. 1746, huile sur toile, Pas d'informations, Collection particulière.

CARRACCI, Annibale

DA VOLTERRA, Daniele (Daniele Ricciarelli)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

RAIMONDI, Marcantonio

Conceptual field(s)

DA VOLTERRA, Daniele (Daniele Ricciarelli), Descente de la croix, v. 1545, fresque, 337 x 221, Roma, Chiesa della Trinità dei Monti.

NATOIRE, Charles-Joseph, L'union de la Peinture et du Dessin, v. 1746, huile sur toile, Pas d'informations, Collection particulière.

CARRACCI, Annibale

DA VOLTERRA, Daniele (Daniele Ricciarelli)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

RAIMONDI, Marcantonio

Conceptual field(s)

DA VOLTERRA, Daniele (Daniele Ricciarelli), Descente de la croix, v. 1545, fresque, 337 x 221, Roma, Chiesa della Trinità dei Monti.

NATOIRE, Charles-Joseph, L'union de la Peinture et du Dessin, v. 1746, huile sur toile, Pas d'informations, Collection particulière.

CARRACCI, Annibale

DA VOLTERRA, Daniele (Daniele Ricciarelli)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

RAIMONDI, Marcantonio

Conceptual field(s)

A Painter’s Language is his Pencil, he should neither say too Little, nor too Much, but go directly to his Point, and tell his Story with all possible Simplicity.

but certainly all the Management in the World cannot put together a great number of Figures, and Ornaments, with that Advantage as a few.

Where the Story requires that there be a Crowd of People, there may be some Figures without any Particular Character, which are not Supernumerary, because the Story requires a Crowd. In the Cartons [ndr : les cartons de Raphaël] there are very few Idle Figures : Nor are all those such that may seem to be so ; there are two in the Carton of S. Paul Preaching that are walking at a distance amongst the Buildings, but these serve well to intimate that there were some who like Gallio cared for none of these things.

Conceptual field(s)

Polydore, in a Drawing I have seen of him, has made an Ill Choice with respect to Decorum ; he has shewn Cato with his Bowels gushing out, which is not only Offensive in itself, but ‘tis a Situation in which Cato should not be seen, ‘tis Indecent ; such things should be left to Imagination, and not display’d on the Stage. But Michelangelo in his last Judgment has sinn’d against this Rule most egregiously.

There are Pictures representing not one particular Story, but the History of Philosophy, of Poetry, of Divinity, the Redemption of Mankind, and the like : Such is the School of Athens, the Parnassus, the Picture in the Vatican commonly call’d the Dispute of the Sacrament, all of Rafaelle ; and the large one of Frederico Zuccaro of the Annunciation, and God the Father, with a Heaven, the Prophets, &c. Such Compositions as These being of a different nature are not subject to the same Rules with Common Historical Pictures ; but Here must be Principal, and Subordonate Figures, and Actions ; As the Plato and Aristotle in the School of Athens, the Apollo in the Parnassus, &c.

Now I have mention’d this Design, I cannot pass it over without going a little out of my way to observe some Particulars of that Admirable Group of the three Poets, Homer, Virgil, and Dante ; […].

The Figure of Homer is an admirably one, and manag’d with great propriety ; He is Group’d with others, but is nevertheless alone :

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio) , Dispute du Très Saint-Sacrement, 1509 - 1510, fresque, 500 × 770, Vatican, Musei Vaticani.

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio) , L'École d'Athènes, 1509 - 1510, fresque, 440 x 770, Vatican, Musei Vaticani.

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio) , Le Parnasse, 1509 - 1511, fresque, Vatican, Musei Vaticani.

Il semblerait que Richardson s'appuie sur une des nombreuses gravures existantes de l'Annonciation de Frederico Zuccaro. Cette dernière œuvre, une fresque, était conservée à l'église Santa Maria Annunziata (Rome), détruite en 1626. Richardson possédait par ailleurs un dessin préparatoire de la fresque réalisé par Zuccaro (voir à ce propos, L. Hamlett, « Italian Baroque Art (Rhetoric, Sublimity) and its British Translations », dans C. van Eyck, Translations of the Sublime: The Early Modern Reception and Dissemination of Longinus' Peri Hupsous in Rhetoric, the Visual Arts, Architecture and the Theatre, 2012, p. 190).

Conceptual field(s)

In all these kinds of Pictures [ndr : images représentant la vie humaine, un trait de caractère d’un individu ou dont le but est de donner une leçon particulière] the Painter should avoid too great a Luxuriancy of Fancy, and Obscurity. The Figures representing any Virtue, Vice, or other Quality, should have such Insignia as are authoriz’d by Antiquity, and Custom ; or if any be necessarily of his Own Invention, his Meaning should be apparent. […]. There are fine Examples of these in the Palace of Chigi, or the little Farnese in Rome ; Rafaëlle has there painted the Fable of Cupid and Psyche, and intermix’d little Loves with the Spoils of all the Gods ; and lastly one with a Lyon, and a Sea-Horse, which he governs as with a Bridle, to shew the Universal Empire of Love.

In Portraits the Invention of the Painter is exercised in the Choice of the Air, and Attitude, the Action, Drapery, and Ornaments, with respect to the Character of the Person.

He ought not to go in a Road, or paint other People as he would choose to be drawn himself. The Dress, the Ornaments, the Colours, must be suited to the Person, and Character.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Many Painters have taken a Fancy to make Caricaturaes of People’s Faces, that is, Exaggerating the Defects, and Concealing the Beauties, however preserving the Resemblance ; the Reverse of That is to be done in the Present Case, but the Character must be seen throughout, or it ceases to be a Compliment ; ’Tis the Picture of Somebody else, or of Nobody, and only tells the Person how different He, or She is from what the Painter conceives to be Beauty.

Conceptual field(s)

I need not go through the other Branches of Painting ; as Landscapes, Battels, Fruit, &c. what has been already said is (Mutatis mutantis) applicable to any of These

There are an Infinity of Artifices to Hide Defects, or Give Advantages, which come under this Head of Invention ; as does all Caprices, Grotesque, and other Ornaments, Masks, &c. together with all Uncommon, and Delicate Thoughts : such as the Cherubims attending on God when he appeared to Moses in the Burning Bush, which Rafaëlle has painted with Flames about them instead of Wings ;

DA VINCI, Leonardo

IL PARMIGIANINO (Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

ROMANO, Giulio

Conceptual field(s)

DA VINCI, Leonardo

IL PARMIGIANINO (Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

ROMANO, Giulio

Conceptual field(s)

DA VINCI, Leonardo

IL PARMIGIANINO (Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

ROMANO, Giulio

Conceptual field(s)

DA VINCI, Leonardo

IL PARMIGIANINO (Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

ROMANO, Giulio

Conceptual field(s)

DA VINCI, Leonardo

IL PARMIGIANINO (Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

ROMANO, Giulio

Conceptual field(s)

The Anatomy Figures in Vesalius said to be design’d by Titian, are prettily fancied : There is a Series of denuding a Figure to the Bone, and they are all in Attitudes seeming to have most Pain as the Operation goes on, till at last they Languish, and Dye : But Michelangelo has made Anatomy Figures whose Faces and Actions are impossible to be describ’d, and the most delicate that can be imagin’d for the purpose.

Of EXPRESSION

Whatever the general Character of the Story is, the Picture must discover it throughout, whether it be Joyous, Melancholy, Grave, Terrible, &c. The Nativity, Resurrection, and Ascension ought to have the General Colouring, the Ornaments, Background, and every thing in them Riant, and Joyous, and the contrary in a Crucifixion, Interment, or a Pietà. [The Blessed Virgin with the dead Christ]. [...] I have seen a fine Instance of a Colouring proper for Melancholy Subjects in a Pietà of Van-Dyck : That alone would make one not only Grave, but sad at first Sight ; And a Colour’d Drawing that I have of the Fall of Phaëton after Giulio Romano, shews how much This contributes to the Expression. ‘Tis different from any Colouring that ever I saw, and admirably adapted to the Subject, there is a Reddish Purple Tinct spread throughout, as if the World was all invelopp’d in Smould’ring Fire.

Of EXPRESSION

Whatever the general Character of the Story is, the Picture must discover it throughout, whether it be Joyous, Melancholy, Grave, Terrible, &c. The Nativity, Resurrection, and Ascension ought to have the General Colouring, the Ornaments, Background, and every thing in them Riant, and Joyous, and the contrary in a Crucifixion, Interment, or a Pietà. [The Blessed Virgin with the dead Christ]. [...] I have seen a fine Instance of a Colouring proper for Melancholy Subjects in a Pietà of Van-Dyck : That alone would make one not only Grave, but sad at first Sight ; And a Colour’d Drawing that I have of the Fall of Phaëton after Giulio Romano, shews how much This contributes to the Expression. ‘Tis different from any Colouring that ever I saw, and admirably adapted to the Subject, there is a Reddish Purple Tinct spread throughout, as if the World was all invelopp’d in Smould’ring Fire.

Conceptual field(s)

Of EXPRESSION

Whatever the general Character of the Story is, the Picture must discover it throughout, whether it be Joyous, Melancholy, Grave, Terrible, &c. The Nativity, Resurrection, and Ascension ought to have the General Colouring, the Ornaments, Background, and every thing in them Riant, and Joyous, and the contrary in a Crucifixion, Interment, or a Pietà. [The Blessed Virgin with the dead Christ].

But a Distinction must be made between Grave, and Melancholy, as in a Holy Family (of Rafaëlle’s Design at least) which I have, and has been mention’d already ; the Colouring is Brown, and Solemn, but yet all together the Picture has not a Dismal Air, but quite otherwise. […] There are certain Sentiments of Awe, and Devotion which ought to be rais’d by the first Sight of Pictures of that Subject, which that Solemn Colouring contributes very much to, but not the more Bright, though upon other Occasions preferable.

I have seen a fine Instance of a Colouring proper for Melancholy Subjects in a Pietà of Van-Dyck : That alone would make one not only Grave, but sad at first Sight ; And a Colour’d Drawing that I have of the Fall of Phaëton after Giulio Romano, shews how much This contributes to the Expression. ‘Tis different from any Colouring that ever I saw, and admirably adapted to the Subject, there is a Reddish Purple Tinct spread throughout, as if the World was all invelopp’d in Smould’ring Fire.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

The Robes, and other Habits of the Figures ; their Attendants, and Ensigns of Authority, or Dignity, as Crowns, Maces, &c. help to express their Distinct Characters ; and commonly even their Place in the Composition. The Principal Persons, and Actors must not be put in a Corner, or towards the Extremities of the Picture, unless the Necessity of the Subject requires it. A Christ, or an Apostle must not be dress’d like an Artificer, or a Fisherman ; a Man of Quality must be distinguish’d from one of the Lower Orders of Men, as a Well-bred Man always is in Life from a Peasant. And so of the rest.

Every body knows the common, or ordinary Distinctions by Dress ; but there is one Instance of a particular kind which I will mention, as being likely to give useful Hints to this purpose, and moreover very curious. In the Carton of Giving the Keys to S. Peter, Our Saviour is wrapt only in on large piece of white Drapery, his Left Arm, and Breast, are part of his Legs naked ; which undoubtedly was done to denote him Now to appear in his Resurrection-Body, and not as before his Crucifixion, when This Dress would have been altogether improper. And this is the more remarkable, as having been done upon second Thoughts, and after the Picture was perhaps finish’d, which I know by having a Drawing of this Carton, very old, and probably made in Rafaëlle’s time, tho’ not of his hand, where the Christ is fully Clad ; he has the very same large Drapery, but one under it that covers his Breast, Arm, and Legs down to the Feet. Every thing else is pretty near the same with the Carton.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Every Figure, and Animal must be affected in the Picture as one should suppose they Would, or Ought to be. And all the Expressions of the several Passions, and Sentiments must be made with regard to the Characters of the Persons moved in them. At the Raising of Lazarus, some may be allow’d to be made to hold something before their Noses, and this would be very just, to denote That Circumstance in the Story, the Time he had been dead ; but this is exceedingly improper in the laying our Lord in the Sepulchre, altho’ he had been dead much longer than he was ; however Pordenone has done it.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Polydore, in a Drawing of the same Subject [ndr : la descente de la croix] […] has finely express’d the Excessive Grief the Virgin, by intimating ‘twas Otherwise Inexpressible : Her Attendants discover abundance of Passion, and Sorrow in their Faces, but Hers is hid by Drapery held up by both her Hands : The whole Figure is very Compos’d, and Quiet ; no Noise, no Outrage, but great Dignity appears in her, suitable to her Character.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

In that admirable Carton of S. Paul preaching, the Expressions are very just, and delicate throughout : Even the Back-Ground is not without its Meaning ; ‘tis Expressive of the Superstition S. Paul was preaching against.

The Airs of the Heads in my Holy Family of Rafaëlle are perfectly fine, according to the several Characters ; that of the Blessed Mother of God has all the Sweetness, and Goodness that could possibly appear in her self ; what is particularly remarkable is that the Christ, and the S. John are both Boys, but the latter is apparently Humane, the other, as it ought to be, Divine.

Conceptual field(s)

In Portraits it must be seen whether the Person is Grave, Gay, a Man of Business, or Wit, Plain, Gentile, &c. Each Character must have an Attitude, and Dress ; the Ornaments and Back-Ground proper to it : Every part of the Portrait, and all about it must be Expressive of the Man, and have a Resemblance as well as the Features of the Face.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Robes, or other Marks of Dignity, or of a Profession, Employment, or Amusement, a Book, a Ship, a Favourite Dog, or the like, are Historical Expressions common in Portraits, which must be mention’d on this occasion ;

The truth is, ‘tis a little choquing to see such a Mixture of Antique, and Modern Figures, of Christianity, and Heathenism in the same Pictures [ndr : Le cycle de Marie de Médicis par Rubens] ; but this is much owing to its Novelty. […] He had moreover Another very good Reason for what he did on this Occasion : The Stories he had to paint were Modern, and the Habits, and Ornaments must be so too, which would not have had a very agreeable effect in Painting : These Allegorical Additions make a wonderful Improvement ; they vary, enliven, and enrich the Work ; as any one may perceive that will imagine the Pictures as they must have been, had Rubens been terrified by the Objections which he certainly must have foreseen would be made afterwards, and so had left all these Heathen Gods, and Goddesses, and the rest of the Fictitious Figures out of the Composition.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

I will add but one way of Expression more, and that is, plain Writing.

Polygnotos, in the Paintings made by him in the Temple of Delphos, wrote the Names of those whom he represented.

The old Italian, and German Masters improv’d upon this ; the Figures they made were Speaking Figures, they had Labels coming out of their Mouths with that written in them which they were intended to be made to say ; but even Rafaëlle, and Annibale Carracci, have condescended to Write rather than leave any Ambiguity, or Obscurity in their Work : Thus the Name of Sappho is written to shew ‘twas She, and not one of the Muses intended in the Parnassus : And in the Gallery Farnese, that Anchises might not be mistaken for Adonis, Genus unde Latinum was written.

Of COMPOSITION

THIS is putting together for the Advantage of the Whole, what shall be judg’d Proper to be the several Parts of a Picture ; either as being Essential to it, or because they are thought necessary for the common Benefit : And moreover, the Determination of the Painter as to certain Attitudes, and Colours which are Otherwise Indifferent.

The Composition of a Picture is of Vast Consequence to the Goodness of it ; ‘Tis what first of all presents it self to the Eye, and prejudices us in Favour Of, or with the Aversion To it ; ‘tis This that directs us to the Ideas that are to be convey’d by the Painter, and in what Order ; and the Eye is Delighted with the Harmony at the same time as the Understanding is Improv’d. Whereas This being Ill, tho’ the several Parts are Fine, the Picture is Troublesome to look upon, and like a Book in which are many Good Thoughts, but flung in confusedly, and without Method.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Every Picture should be so contriv’d, as that at a Distance, when one cannot discern what Figures there are, or what they are doing, it should appear to be composed of Masses, Light, and Dark ; the Latter of which serve as Reposes to the Eye. The Forms of These Masses must be Agreeable, of whatsoever they consist, Ground, Trees, Draperies, Figures, &c. and the Whole together should be Sweet, and Delightful, Lovely Shapes and Colours without a Name ; of which there is an infinite Variety.

And ‘tis not enough that there be Great Masses ; they must be Subdivised into Lesser Parts, or they will appear Heavy, and Disagreeable : Thus tho’ there is evidently a Broad Light (for Example) in a piece of Silk when covering a whole Figure, or a Limb, there may be Lesser Folds, Breakings, Flickerings, and Reflections, and the Great Mass yet evidently preserv’d.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Every Picture should be so contriv’d, as that at a Distance, when one cannot discern what Figures there are, or what they are doing, it should appear to be composed of Masses, Light, and Dark ; the Latter of which serve as Reposes to the Eye. The Forms of These Masses must be Agreeable, of whatsoever they consist, Ground, Trees, Draperies, Figures, &c. and the Whole together should be Sweet, and Delightful, Lovely Shapes and Colours without a Name ; of which there is an infinite Variety.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Sometimes one Mass of Light is upon a dark Ground, and then the Extremities of the Light must not be too near the edges of the Picture, and its greatest Strength must be towards the Centre ; […].

I have a Painting of the Holy Family by Rubens of this Structure ; where, because the Mass of Light in one part would else have gone off too abruptly, and have made a less pleasing Figure, he has set the Foot of S. Elizabeth on a little Stool ; here the Light catches, and spreads the Mass so as to have the desired effect. Such another Artifice Rafaëlle has used in a Madonna, […] ; He has brought in a kind of an Ornament to a Chair for no other end (that I can imagine) but to form the Mass agreeably.

PONTIUS, Paulus, Jésus-Christ en croix, dit aussi « au coup de poing », d'après Rubens, v. 1631, 60,5 x 38, 6, Paris, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Paris, GDUT8222.

VORSTERMAN, Lucas, Descente de la croix d'après Rubens, v. 1620, 58,5 x 42,5, Paris, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Paris, GDUT8226.

Conceptual field(s)

I have many times observ’d with a great deal of Pleasure the admirable Composition (besides other Excellencies) of a Fruit-piece of Michelangelo Compadoglio, which I have had many Years. The principal Light is near the Centre (not Exactly there, for those Regularities have an ill effect ;) and the Transition from thence, and from one thing to another, to the Extremities of the Picture all round is very Easy, and Delightful ; in which he has employ’d fine Artifices by Leaves, Twigs, little Touches of Lights striking advantageously, and the like. So that there is not a Stroke in the Picture without its Meaning ; and the whole, tho’ very Bright, and consisting of a great many Parts, has a wonderful Harmony, and Repose.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Sometimes the Structure of a Picture, or the Tout-Ensemble of its Form, shall resemble dark Clouds on a Light Ground ; As in two Assumptions of the Virgin by Bolswert after Rubens ; indeed a part of These are such Clouds : But in both of them the Figures of these Masses are something too Indistinct. Le Brun in a Ceiling of the same Subject, grav’d, by young Simconneau, has put a Group of Angels, which almost hide the cloudy Voiture of the Virgin ; but this mass is too Regular, and Heavy a Shape.

Conceptual field(s)

Sometimes the Structure of a Picture, or the Tout-Ensemble of its Form, shall resemble dark Clouds on a Light Ground ; As in two Assumptions of the Virgin by Bolswert after Rubens ; indeed a part of These are such Clouds : But in both of them the Figures of these Masses are something too Indistinct. Le Brun in a Ceiling of the same Subject, grav’d, by young Simconneau, has put a Group of Angels, which almost hide the cloudy Voiture of the Virgin ; but this mass is too Regular, and Heavy a Shape. I refer you to Prints, because they are easy to be got, and explain This matter as well as Drawings, or Pictures, and in some Respects Better.

Conceptual field(s)

There are Instances where two Masses ; a Light, and a Dark one, divide the Picture, each possessing One Side. I have of This sort by Rubens, and as fine a Composition as can be seen ; the Masses are so well Rounded, the Principal Light being near the Middle of the Bright One, and the Other having Subordinate Lights upon it so as to Connect, but not to Confound it with the rest ; and they are in agreeable Shapes, and melting into One Another, but nevertheless sufficiently determined.

Very commonly a Picture consists of a Mass of Light, and another of Shadow upon a Ground of a Middle Tinct. And sometimes ‘tis composed of a Mass of Dark at the bottom, another Lighter above that, and another for the upper part still Lighter ; (as usually in a Landscape) Sometimes the Dark Mass employs one Side of the Picture also.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

There are Instances where two Masses ; a Light, and a Dark one, divide the Picture, each possessing One Side. I have of This sort by Rubens, and as fine a Composition as can be seen ; the Masses are so well Rounded, the Principal Light being near the Middle of the Bright One, and the Other having Subordinate Lights upon it so as to Connect, but not to Confound it with the rest ; and they are in agreeable Shapes, and melting into One Another, but nevertheless sufficiently determined.

Very commonly a Picture consists of a Mass of Light, and another of Shadow upon a Ground of a Middle Tinct. And sometimes ‘tis composed of a Mass of Dark at the bottom, another Lighter above that, and another for the upper part still Lighter ; (as usually in a Landscape) Sometimes the Dark Mass employs one Side of the Picture also. I have a Copy after Paolo Veronese where a large Group of Figures, the principal ones of the Story, compose this lower brown Mass ; Architecture, the second ; more Buildings, with Figures and the Sky, the third ; but most commonly in Pictures of Three Masses, the Second is the Place of the Principal Figures.

As the Tout-ensemble of a Picture must be Beautiful in its Masses, so must it be as to its Colours. And as what is Principal must be (Generally speaking) the most Conspicuous, the Predominant Colours of That should be diffus’d throughout the Whole. This Rafaëlle has observ’d remarkably in the Carton of S. Paul Preaching ; His Drapery is Red, and Green, and These Colours are scatterr’d every where ; but Judiciously ; for Subordinate Colours as well as Subordinate Lights serve to Soften, and Support the Principal ones, which Otherwise would appear as Spots, and consequently be Offensive.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

In a Figure, and every part of a Figure, and indeed in every thing else there is One part which must have a peculiar Force, and be manifestly distinguish’d from the rest, all the Other parts of Which must also have a due Subordination to It, and to One Another. The same must be observ’d in the Composition of an entire Picture ; And this Principal, Distinguis’d part ought (Generally speaking) to be the Place of the Principal Figure, and Action : And Here every thing must be higher Finish’d, the Other parts must be Less so Gradually.

Pictures should be like Bunches of Grapes, but they must not resemble a great many single Grapes scatter’d on a Table ; there must not be many little Parts of an Equal Strength, and detach’d from one another, which is as odious to the Eye as ‘tis to the Ear to hear many People talking to you at once. Nothing must Start, or be too strong for the Place where it is as in a Confort of Musick when a Note is too high, or an Instrument out of Tune ; but a sweet Harmony and Repose must result from all the Parts judiciously put together, and united with each other.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Ananias is the Principal Figure in the Carton which gives the History of his Death ; as the Apostle that pronounces his Sentence is of the Subordinate Group, which consists of Apostles. (Which therefore is Subordinate Group, because the Principal Action relates to the Criminal, and thither the Eye is directed by almost all the Figures in the Picture.) S. Paul is the chief Figure in that Carton where he is Preaching, and amongst his Auditors One is eminently distinguish’d, who is Principal of that Group ; and is apparently a Believer, and More so than any of them, or he had not had that Second Place in a Picture conducted by so great a Judgment as that of Rafaëlle’s. These Principal, and Subordinate Groupes, and Figures, are so apparent, that the Eye will naturally fix first upon one, then upon the other, and consider each in Order, and with Delight.

And sometimes the Painter happens to be Obliged to put a Figure in a Place, and with a Degree of Force which does not sufficiently distinguish it. In that Case, the Attention must be awakened by the Colour of its Drapery, or a Part of it, or by the Ground on which ‘tis painted, or some other Artifice.

Scarlet, or some Vivid Colour, is very proper on such Occasions : I think I have met with an Instance of This kind from Titian, in a Bacchus and Ariadne ; Her Figure is Thus distinguish’d for the reason I have given.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

In a Composition, as well as in every Single Figure, or other part of which the Picture consists, one thing must Contrast, or be varied from another.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

In a Composition, as well as in every Single Figure, or other part of which the Picture consists, one thing must Contrast, or be varied from another. Thus in a Figure, the Arms and Legs must not be placed to answer one another in Parallel Lines. In like manner if one Figure in a Composition Stands, another must Bend, or Lye on the Ground ; and of those that Stand, or are in any other Position, if there be several of them, they must be varied by Turns of the Head, or some other Artful Disposition of their Parts ; as may be seen (for instance) in the Carton of giving the Keys. The Masses must also have the like Contrast, two must not be alike in Form, or Size, nor the whole Mass compos’d of those lesser ones of too Regular a Shape. [...] All which, together with several other Particulars, produce a wonderful Harmony.

Conceptual field(s)

In a Composition, as well as in every Single Figure, or other part of which the Picture consists, one thing must Contrast, or be varied from another. Thus in a Figure, the Arms and Legs must not be placed to answer one another in Parallel Lines. In like manner if one Figure in a Composition Stands, another must Bend, or Lye on the Ground ; and of those that Stand, or are in any other Position, if there be several of them, they must be varied by Turns of the Head, or some other Artful Disposition of their Parts ; as may be seen (for instance) in the Carton of giving the Keys. The Masses must also have the like Contrast, two must not be alike in Form, or Size, nor the whole Mass compos’d of those lesser ones of too Regular a Shape. The Colours must be also Contrasted, and Oppos’d, so as to be grateful to the Eye : There must not (for example) be two Draperies in one Picture of the same Colour, and Strength, unless they are contiguous, and then they are but as one. If there be two Reds, Blews, or whatever other Colour, One must be of a Darker, or Paler Tinct, or be some way Varied by Lights, Shadows, of Reflections. Rafaëlle, and others have made great Advantage of Changeable Silks to unite the Contrasting Colours, as well as to make a part of the Contrast themselves. As in the Carton of Giving the Keys, the Apostle that stands in Profile, and immediately behind S. John, has a Yellow Garment with Red Sleeves, which connects that Figure with S. Peter, and S. John, whose Draperies are of the same Species of Colours. Then the same Anonymous Apostle has a loose changeable Drapery, the Lights of which are a Mixture of Red, and Yellow, the other Parts are Bluish. This Unites it self with the Other Colours already mentioned, and with the Blew Drapery of another Apostle which follows afterwards ; between which, and the changeable Silk is a Yellow Drapery something different from the other Yellows, but with Shadows bearing upon the Purple, as those of the Yellow Drapery of S. Peter incline to the Red : All which, together with several other Particulars, produce a wonderful Harmony.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

The Colours must be also Contrasted, and Oppos’d, so as to be grateful to the Eye : There must not (for example) be two Draperies in one Picture of the same Colour, and Strength, unless they are contiguous, and then they are but as one. If there be two Reds, Blews, or whatever other Colour, One must be of a Darker, or Paler Tinct, or be some way Varied by Lights, Shadows, of Reflections. Rafaëlle, and others have made great Advantage of Changeable Silks to unite the Contrasting Colours, as well as to make a part of the Contrast themselves. As in the Carton of Giving the Keys, the Apostle that stands in Profile, and immediately behind S. John, has a Yellow Garment with Red Sleeves, which connects that Figure with S. Peter, and S. John, whose Draperies are of the same Species of Colours. Then the same Anonymous Apostle has a loose changeable Drapery, the Lights of which are a Mixture of Red, and Yellow, the other Parts are Bluish. This Unites it self with the Other Colours already mentioned, and with the Blew Drapery of another Apostle which follows afterwards ; between which, and the changeable Silk is a Yellow Drapery something different from the other Yellows, but with Shadows bearing upon the Purple, as those of the Yellow Drapery of S. Peter incline to the Red : All which, together with several other Particulars, produce a wonderful Harmony.

Conceptual field(s)

Tho’ a Mass may consist of a Number of Little Parts, there ought to be one, or more, Larger, and as it were governing the rest, and this is another sort of Contrast. My Lord Burlington has a Good Samaritan by Bassau, which is a fine Instance of This. In the same Picture, there are two knees of two several Figures, pretty near together, and the Legs and Thighs of which make Angles too much alike, but this is contracted by one being Naked, and the other Clad, and over the latter, a little sort of Sash falls, which is an additional Expedient.

This important piece of Drapery preserves the Mass of Light upon that Figure [ndr : il s’agit de la draperie de saint Paul dans le carton de Saint Paul prêchant à Athènes par Raphaël], but varies it, and gives it an agreeable Form, whereas without it the whole Figure would have been Heavy, and Disagreeable ; but there was no danger of that in Rafaëlle. There is another piece of Drapery in the Carton of Giving the Keys, which is very Judiciously flung in ; The three outmost Figures at the End of the Picture, (the contrary to that where our Lord is) made a Mass of Light of a Shape not very pleasing, till that knowing Painter struck in a part of the Garment of the last Apostle in the Group as folded under his Arm, this breaks the streight Line, and gives a more grateful Form to the whole Mass ;

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio) , Le Christ donnant les clefs du Paradis à saint Pierre, 1516 - 1516, gouache et huile sur carton, 340 x 530, London, Victoria & Albert Museum,

ROYAL LOANS.3.

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio) , Saint Paul prêchant à Athènes, 1516, dessin et peinture à l'eau, 340 x 440, London, Victoria & Albert Museum, ROYAL LOANS.7.

Conceptual field(s)

The Masters to be studied for Composition are Rafaëlle, Rubens and Rembrandt most especially, tho’ many others are worthy notice, and to be carefully consider’d ; amongst which V. Velde ought not to be forgottten, who tho’ his Subjects were Ships, which consisting of so many little parts, are very difficult to fling into great Masses, has done it, by the help of spread Sails, Smoak, and the Bodies of the Vessels, and a judicious Management of Lights and Shadows. So that His Compositions are many times as good as those of any Master.

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

REMBRANDT (Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn)

RUBENS, Peter Paul

VAN DE VELDE, Willem le Jeune

Conceptual field(s)

DESIGN or DRAWING

By these Terms is sometimes understood the expressing our Thoughts upon Paper, or whatever other flat Superficies ; and that by Resemblances form’d by a Pen, Crayon, Chalk, or the like. But more commonly, The giving the Just Form, and Dimension of Visible Objects, according as they appear to the Eye ; if they are pretended to be describ’d in their Natural Dimensions ; If Not, but Bigger, or Lesser, then Drawing, or Designing signifies only the giving those Things their true Form, which implies an exact proportionable Magnifying, or Diminishing in every part alike

And this comprehends also giving the true Shapes, Places, and even Degrees of Lights, Shadows, and Reflections ; because if these are not right, if the thing has not its due Force, or Relief, the true Form of what is pretended to be drawn cannot be given : These shew the Out-Line all round, and in every part, as well as where the Object is terminated on its Back-Ground.

In a Composition of several Figures, or whatever other Bodies, if the Perspective is not just the Drawing of that Composition is false. This therefore is also imply’d by this Term. That the Perspective must be observ’d in the Drawing of a Single Figure cannot be doubted.

I know Drawing is not commonly understood to comprehend the Clair-obscure, Relief, and Perspective, but it does not follow however that what I advance is not right.

Conceptual field(s)

DESIGN or DRAWING

By these Terms is sometimes understood the expressing our Thoughts upon Paper, or whatever other flat Superficies ; and that by Resemblances form’d by a Pen, Crayon, Chalk, or the like. But more commonly, The giving the Just Form, and Dimension of Visible Objects, according as they appear to the Eye ; if they are pretended to be describ’d in their Natural Dimensions ; If Not, but Bigger, or Lesser, then Drawing, or Designing signifies only the giving those Things their true Form, which implies an exact proportionable Magnifying, or Diminishing in every part alike

And this comprehends also giving the true Shapes, Places, and even Degrees of Lights, Shadows, and Reflections ; because if these are not right, if the thing has not its due Force, or Relief, the true Form of what is pretended to be drawn cannot be given : These shew the Out-Line all round, and in every part, as well as where the Object is terminated on its Back-Ground.

DESIGN or DRAWING

By these Terms is sometimes understood the expressing our Thoughts upon Paper, or whatever other flat Superficies ; and that by Resemblances form’d by a Pen, Crayon, Chalk, or the like. But more commonly, The giving the Just Form, and Dimension of Visible Objects, according as they appear to the Eye ; if they are pretended to be describ’d in their Natural Dimensions ; If Not, but Bigger, or Lesser, then Drawing, or Designing signifies only the giving those Things their true Form, which implies an exact proportionable Magnifying, or Diminishing in every part alike

And this comprehends also giving the true Shapes, Places, and even Degrees of Lights, Shadows, and Reflections ; because if these are not right, if the thing has not its due Force, or Relief, the true Form of what is pretended to be drawn cannot be given : These shew the Out-Line all round, and in every part, as well as where the Object is terminated on its Back-Ground.

In a Composition of several Figures, or whatever other Bodies, if the Perspective is not just the Drawing of that Composition is false. This therefore is also imply’d by this Term. That the Perspective must be observ’d in the Drawing of a Single Figure cannot be doubted.

I know Drawing is not commonly understood to comprehend the Clair-obscure, Relief, and Perspective, but it does not follow however that what I advance is not right.

But if the Out-Lines are only mark’d, this also is Drawing ; ‘tis giving the true Form of what is pretended to, that is, the Out-Line.

The Drawing in the latter, and most common Sense ; besides that it must be Just, must be pronounced Boldly, Clearly, and without Ambiguity : Consequently, neither the Out-Lines, nor the Forms of the Lights, and Shadows must be Confus’d, and Uncertain, or Wooly (as Painters call it) upon pretence of Softness ; nor on the other hand may they be Sharp, Hard, or Dry ; for either of these are Extreams ; Nature lies between them.

Conceptual field(s)

But if the Out-Lines are only mark’d, this also is Drawing ; ‘tis giving the true Form of what is pretended to, that is, the Out-Line.

The Drawing in the latter, and most common Sense ; besides that it must be Just, must be pronounced Boldly, Clearly, and without Ambiguity : Consequently, neither the Out-Lines, nor the Forms of the Lights, and Shadows must be Confus’d, and Uncertain, or Wooly (as Painters call it) upon pretence of Softness ; nor on the other hand may they be Sharp, Hard, or Dry ; for either of these are Extreams ; Nature lies between them.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

So neither are there two Men, nor two Faces, no, not two Eyes, Foreheads, Noses, or any other Features : Nay farther, there is not two Leaves, tho’ of the same Species, perfectly alike.

A Designer therefore must consider, when he draws after Nature, that his Business is to describe That very Form, as distinguish’d from every other Form in the Universe.

In order to give this Just Representation of Nature […] I say in order to follow Nature exactly, a Man must be well acquainted with Nature, and have a reasonable Knowledge of Geometry, Proportion, (which must be varied according to the Sex, Age, and Quality of the Person) Anatomy, Osteology, and Perspective. I will add to these an Acquaintance with the Works of the best Painters, and Sculptors, Ancient, and Modern : For ‘tis a certain Maxim, No Man sees what things Are, that knows not what they Ought to be.

That this Maxim is true, will appear by an Academy Figure drawn by one ignorant in the Structure, and knitting of the Bones, and Anatomy, compar’d with another who understands these throughly :

Conceptual field(s)

In order to give this Just Representation of Nature […] I say in order to follow Nature exactly, a Man must be well acquainted with Nature, and have a reasonable Knowledge of Geometry, Proportion, (which must be varied according to the Sex, Age, and Quality of the Person) Anatomy, Osteology, and Perspective. I will add to these an Acquaintance with the Works of the best Painters, and Sculptors, Ancient, and Modern : For ‘tis a certain Maxim, No Man sees what things Are, that knows not what they Ought to be.

That this Maxim is true, will appear by an Academy Figure drawn by one ignorant in the Structure, and knitting of the Bones, and Anatomy, compar’d with another who understands these throughly :

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

When a Painter intends to make a History (for example) the way commonly is to design the thing in his Mind, to consider what Figures to bring in, and what they are to Think, Say, or Do ; and then to Sketch upon Paper this Idea of his ; and not only the Invention, but Composition of his intended Picture : This he may alter upon the same Paper, or by making other Sketches, till he is pretty well determin’d as to that ; (and this is that first Sense in which I said the Term Drawing, or Designing was to be understood.)

Conceptual field(s)

When a Painter intends to make a History (for example) the way commonly is to design the thing in his Mind, to consider what Figures to bring in, and what they are to Think, Say, or Do ; and then to Sketch upon Paper this Idea of his ; and not only the Invention, but Composition of his intended Picture : This he may alter upon the same Paper, or by making other Sketches, till he is pretty well determin’d as to that ; (and this is that first Sense in which I said the Term Drawing, or Designing was to be understood.) In the next place his Business is to consult the Life, and to make Drawings of particular Figures, or parts of Figures, or of what else he intends to bring into his Work, as he finds necessary ; together also with such Ornaments, or other things of his Invention, as Vases, Frizes, Trophies, &c. till he has brought his Picture to some Perfection on Paper, either in these loose Studies, or in one entire Drawing. This is frequently done, and sometimes these Drawings are finish’d very highly by the Master, either that his Disciples might be able from them to make a greater Progress in the Grand Work, and so leave the less for Himself to do ; or because he made Advantage of such Drawings from the Person who employ’d him, or some other ; and perhaps sometimes for his own Pleasure.

Of these Drawings of all kinds, those great Masters […] made very many ; sometimes several for the same thing, and not only for the same Picture, but for one Figure, or part of a Figure ; and though too many are perish’d, and lost, a considerable Number have escap’d, and been preserved to our Times, some very well, others not, as it has happen’d : And these are exceedingly priz’d by all who understand, and can see their Beauty ; for they are the very Spirit, and Quintessence of the Art ; there we see the Steps the Master took, the Materials with which he made his Finish’d Paintings, which are little other than Copies of these, and frequently (at least in part) by some Other Hand ; but these are undoubtedly altogether his Own and true, and proper Originals.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)