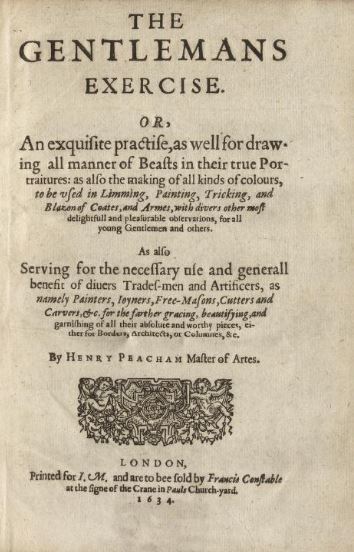

PEACHAM, Henry, The Gentlemans Exercise. Or, An exquisite practise, as well for drawing all manner of Beasts in their true Portraitures : as also the making of all kinds of colours, to be used in Limning, Painting, Tricking, and Blazon of Coates, and Armes, with divers other most delightfull and pleasurable observations, for all young Gentlemen and others. As also Serving for the necessary use and generall benefit of divers Trades-men and Artificers, as namely Painters, Ioners, Free-Masons, Cutters and Carvers, &c. for the farther gracing, beautifying, and garnishing of all their absolute and worthy pieces, either for Borders, Architects, or Columnes, &c., London, J. Legat, 1634.

Peacham est l’auteur d’ouvrages sur divers sujets : peinture et dessin, emblèmes – il publie notamment en 1612, Minerva Britanna or a Garden of Heroical Devises. En 1634, il publie également son traité le plus connu, The Compleat Gentleman, dans lequel il évoque l’ensemble des disciplines auxquelles un gentleman doit s'intéresser (poésie, peinture, pêche, voyage, blasons, etc.) [2].

Concernant plus directement ses traités sur l’art, Peacham publie en 1606 un manuel dédié au dessin et adressé à un public non-connaisseur – le premier en anglais selon F. J. Levy – : The Art of Drawing with the Pen, and Limning in Water Colour, texte réédité l’année suivante [3]. Deux éditions enrichies paraissent par la suite : la première en 1612, intitulée Graphice or the most ancient and excellent Art of Drawing and Limning, la seconde en 1634, The Gentleman’s Exercise [4]. Ces deux dernières éditions contiennent des chapitres supplémentaires par rapport à The Art of Drawing, comme celui sur la perspective, de même que des développements, en particulier sur les pigments. Peacham précise en effet les étymologies des couleurs et leurs équivalences en latin, allemand, français, italien, ou encore néerlandais [5].

Graphice et The Gentleman’s Exercise comprennent trois parties. Dans la première, Peacham fournit des conseils sur la pratique du dessin et de la miniature (choix des instruments, manière de dessiner un visage, fabrication des pigments, etc.). Il ajoute parfois des petits dessins pour illustrer son propos, comme dans le chapitre sur le traitement des ombres. La deuxième partie de ces ouvrages porte sur l’iconographie. Peacham y explique ainsi les attributs de diverses allégories. Enfin, la dernière partie est consacrée aux blasons.

Le but de Peacham est notamment de montrer l’intérêt du dessin à ses lecteurs, mais aussi de donner quelques éléments de base permettant de pratiquer cet art. Selon Peacham, le dessin était un passe-temps utile, mais il permet aussi à un gentleman de bien juger les œuvres d’art [6]. Par ailleurs, Peacham déplore le manque de patrons pour les arts en Angleterre. En 1634, dans sa dédicace à Sir Edmund Ashfield, il critique ainsi le peu d’encouragements donnés aux artistes.

Toutefois, comme le note F. J. Levy, The Gentlemans Exercise est davantage un assemblage de divers textes qu’un véritable traité artistique. Peacham cite en effet de nombreux auteurs : Aristote, Vitruve, Pline l’ancien, Van Mander, etc. [7]. Il mentionne en outre Lomazzo, qu’il devait sûrement connaître à travers la traduction qu’en fit Haydocke en 1598. Il évoque en effet le théoricien italien à différentes reprises, et notamment dans son chapitre sur l’expression des passions [8]. De même, Peacham cite à de multiples reprises Scaliger dans ses chapitres sur la couleur et les pigments.

Élodie Cayuela

[1] Pour plus de détails sur la vie de Peacham, voir J. Horden, « Peacham, Henry (b. 1578, d. in or after 1644) », Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/21667, consulté le 25 octobre 2016].

[2] Sur ce texte, son contexte et la tradition du courtisan instaurée par Castiglione, voir notamment L. Salerno, 1951, p. 236-237 et A. Bermingham, 2000, p. 33-68.

[3] F. J. Levy, 1974, p. 178.

[4] Ce texte est défini par J. Horden comme « one of Peacham’s most widely read works » (op. cit.)

[5] Sur les évolutions entre les différentes éditions, voir F. J. Levy, 1974, p. 182-184.

[6] Pour plus de détails, voir F. J. Levy, 1974, p. 189 et suivantes.

[7] L. F. Levy, 1974, p. 190.

[8] Peacham, 1634, p. 27. Sur l’influence de Lomazzo sur Peacham, voir L. Semler, 2004, p. 740-743.

PEACHAM, Henry, The Art of Drawing with the Pen, and Limning in Water Colours, more exactlie then heretofore taught and enlarged with the true manner of Painting upon glasse, the order of making your furnace, Annealing, &c. Published, For the behoofe of all young Gentlemen, or any els that are desirous for to become practicioners in this excellent, and most ingenious Art, London, Richard Braddock, 1606.

PEACHAM, Henry, The Art of Drawing with the Pen, and Limning in Water Colours, More Exactlie then heretofore taught and enlarged with the true manner of Painting upon glasse, the order of making your furnace, Annealing, &c. Published, For the behoofe of all young Gentlemen, or any els that are desirous for to become practicioners in this excellent, and most ingenious Art, London, Richard Braddock, 1607.

PEACHAM, Henry, The Gentlemans Exercise. Or, An exquisite practise, as well for drawing all manner of Beasts in their true Portraitures : as also the making of all kinds of colours, to be used in Limning, Painting, Tricking, and Blazon of Coates, and Armes, with divers other most delightfull and pleasurable observations, for all young Gentlemen and others. As also Serving for the necessary use and generall benefit of divers Trades-men and Artificers, as namely Painters, Ioners, Free-Masons, Cutters and Carvers, &c. for the farther gracing, beautifying, and garnishing of all their absolute and worthy pieces, either for Borders, Architects, or Columnes, &c., London, I. Browne, 1612.

PEACHAM, Henry, The Art of Drawing with the Pen, Amsterdam - New York, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum - Da Capo Press, 1970.

SALERNO, Luigi, « Seventeenth-Century English Literature on Painting », Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 14/3-4, 1951, p. 234-258 [En ligne : http://www.jstor.org/stable/750341 consulté le 30/03/2018].

LEVY, F. J., « Henry Peacham and the Art of Drawing », Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 37, 1974, p. 174-190 [En ligne : http://www.jstor.org/stable/750839 consulté le 30/03/2018].

YOUNG, Alan R., Henry Peacham, Boston, Twayne Publishers, 1979.

MARTINET, Marie-Madeleine, « L'espace dans la peinture anglaise aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles : perspective de l'esprit et distance affective », Espaces et représentations dans le monde anglo-américain aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, Actes du colloque de Paris, Paris, Presses de l'université Paris-Sorbonne, 1981, p. 62-82.

YOUNG, Alan R., « Henry Peacham, Ripa's "Iconologia", and Vasari's "Lives" », Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme, 9/3, 1985, p. 177-188 [En ligne : http://www.jstor.org/stable/43444538 consulté le 30/03/2018].

WHITE, Christopher, « The Theory and Practice of Drawing in Early Stuart England », dans WHITE, Christopher et STAINTON, Lindsay (éd.), Drawing in England from Hilliard to Hogarth, cat. exp., London, British Museum - New Haven, Yale Center for British Art, 1987, Cambridge - New Haven, Cambridge University Press, 1987, p. 13-28.

SCHLUETER, June, « Rereading the Peacham Drawing », Shakespeare Quarterly, 50/2, 1999, p. 171-184 [En ligne : https://ldr.lafayette.edu/bitstream/handle/10385/631/Schlueter-ShakespeareQuarterly-vol50-no2-1999.pdf?sequence=1 consulté le 30/03/2018].

BERMINGHAM, Ann, Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art, New Haven - London, Yale University Press, 2000.

HARLEY, Rosamond Drusilla, Artists' Pigments c.1600-1835: A Study in English Documentary Sources, London, Archetype Publications Ltd, 2001.

SEMLER, Liam E., « Breaking the Ice to Invention: Henry Peacham's "The Art of Drawing" (1606) », The Sixteenth Century Journal, 35/3, 2004, p. 735-750 [En ligne : http://www.jstor.org/stable/20477043 consulté le 30/03/2018].

HURLEY, Cecilia, « Englishing Vasari », dans LUCAS FIORATO, Corinne et DUBUS, Pascale (éd.), La Réception des Vite de Giorgio Vasari dans l'Europe des XVIe-XVIIIe siècles, Actes du colloque de Paris, Genève, Droz, 2017, p. 409-425.

FILTERS

QUOTATIONS

Painting in generall called in Latine Pictura, in Greeke χρωματική, is an Art, which either by draught of bare lines, lively colours, cutting out or embossing, expresseth any thing the like by the same : which we may finde in the holy Scripture both allowed and highly commended by the mouth of God himselfe, where he calleth Bezaleel and Aholia {Exodus 31.}, men whom he hath filled with the spirit of God in wisedome and understanding, and in knowledge, and in all workmanship, to find out curious works, to worke in gold, and in silver, and in brasse, also in the art to set stones, and to carve in timber, &c. There plainly shewing, as all other good Arts, so carving or drawing to be an especiall gift of Gods Spirit.

But some will tell me, Mechanicall Arts, and those wrought with the hand are for the most part base, and unworthy the practise of great personages, and Gentlemen […]. But forasmuch as their ends are honest, and themselves but the exercises of pregnant and the finest wits, I see no reason (as one saith) why nature should be so much wronged in her intention, as not to produce at her pleasure that into action whereto shee is well inclined {Exam. de Ingenios.}. And surely it can bee no more disgrace to a great Lord to draw a faire Picture, then to cut his Hawkes meate, or play at Tennis with his Page. […].

Pomponius Atticus a man of singular wisedome, and so much beloved of Cicero, after he had composed a Poeme of sundry devises, beautified the same with pictures of his owne Drawing.

[…]. Since Painting then hath beene so well esteemed, and of it owne nature is so linked with the other Arts, as many of them can hardly stand without it. I thinke it not for pleasure onely, but of necessitie most needfull to be practised of all such, that either studie the Mathematikes, the art Military, or purpose to travell for the benefit of their friends and countrey. I have heard many excellent Captaines and Schollers lament so great a want in themselves, otherwise being most absolute.

My Scholler then I would make choise of, should be a young Gentleman, if it might be, naturally inclined to drawing, at least a welwiller and lover of it.

Pyreicus (as Volaterane saith) was onely famous for counterfeiting all base things as earthen pitchers, a scullery, Rogues together by the eares, swine tumbling in the mire, &c. whereupon he was sirnamed Rupographus. {That is Painter of base things.}

Conceptual field(s)

Aristides was the most excellent of his time for expressing sence and passion, as in that peece of his, of a mother deadly wounded, and giving her child sucke, in whose face he expressed a deadly feare, as loath to deny it food, and unwilling to give it the teate for feare of killing it with her blood, which with the milke issued forth in great abundance. This Table Alexander carried with him to Pella.

Of Drawing the Face or countenance of a Man.

[…]

The visage or countenance is (for the most part) drawn but three manner of wayes, the first is full faced, […] {The full face.}

The second is three quarter faced, as our Flanders and ordinary pictures are, that is when one part of the face is hid by a quarter as thus : [ndr : insertion d’un dessin explicatif].

{Halfe face.} The third is onely halfe faced, […] as this Cæsars head [ndr : présence d’un dessin accôlé au texte illustrant le propos de Peacham].

The passions of the minde being divers as love, feare, joy, anger, hatred, despaire, desire, boldnesse, &c. must be expressed with great judgement and discretion, though you shall better expresse them in lively colours then with the pen, because palenesse, rednesse, fiery eyes, &c. are adjuncts to the same.

A Shadow is nothing else but a diminution of the first and second light.

The first light I call that which proceedeth immediately from a lightned body, as the beames of the Sunne.

The second is an accidental light dispreading it self into the aire or medium, proceeding from the other.

Under this division are comprehended the other lights, as the light of glory is referred to the first. The light of all manner of reflexions to the second.

Shadowes are threefold : the first is a single shadow, and the least of all other, and is proper to the plaine Superficies, where it is not wholy possessed of the light ; as for example.

I draw a foure square plate thus, that shadow, because there is no hollow, but all plaine (as neerest participating with the light) is most naturall and agreeable to that body.

The second is the double shadow, and it is used when the Superficies begins once to forsake your eyes as you may perceive best in columnes as thus : where it beeing darkened double, it presenteth to your eye (as it were) the backside, leaving that unshadowed to the light. Your treble shadow is made by crossing over your double shadow againe, which darkeneth by a third part in this manner, as followeth. [ndr : les deux types d’ombres sont illustrés par des petits dessins accolés au texte].

Generall rules for shadowing.

You must alwayes cast your shadow one way, that is, on which side of the body you begin your shadow, you must continue it till your worke be done : as if I would draw a man, I begin to shadow his left cheeke, the left part of his necke, […] leaving the other to the light, except the light side be darkned by the opposition of another body, […].

2. All circular and round bodies that receive a concentration of the light, […] must be shadowed in circular manner as thus : [ndr: insertion d’un dessin explicatif dans le corps du texte].

3. All perfect lights doe receive no shadow at all, therefore hee did absurdly, that in the transfiguration of our Saviour in the Mount, gave not his garments a deepe shadow, but also thinking to shew great Art, hee gave the beames of the light it selfe a deeper, both which ought to have beene most glorious, and all meanes used for their lustre and brightnesse; which hath beene excellently well observed of Stradane and Goltzius.

4. Where contrary shadowes concurre and strive […] let the neerest and most solide body be first served. […].

5. It will seeme a hard matter to shadow a gemme or well pointed Diamond, […] : but if you observe the rules of the light which I shall give you, you shall easily doe it without difficultie.

6. All shadowes participate in the medium according to the greatnesse or weakenesse of the light.

7. No body betweene the light, and our sight can effect an absolute darkenesse, wherefore I said a shadow was but a diminution of the light, and it is a great question whether there be any darknesse in the world or not.

Of Foreshortning

The chiefe use of perspective you have in foreshortning, which is when by art the whole is concluded into one part, which onely shall appeare to the sight, as if I should paint a ship upon the Sea, yet there should appeare unto you but her forepart, the rest imagined hid, or likewise an horse with his brest and head looking full in my face, I must of necessity foreshorten him behind, because his sides and flankes appeare not unto me : this kind of draught is willingly overslipt by ordinary painters for want of cunning and skill to performe it ; and you shall see not one thing among a hundred among them drawne in this manner, but after the ordinary fashion side-wayes, and that but lamely neither.

The use of it is to expresse all manner of action in man or beast, to represent many things in a little roome, to give or shew sundry sides of Cities, Castles, Forts, &c. at one time.

Conceptual field(s)

Landtskip is a Dutch word, and it is as much as we should say in English Landship, or expressing of the land by hilles, woods, castles, seas, vallies, ruines, hanging rockes, cities, townes, &c. as farre as may bee shewed within our Horizon. If it be not drawne by it selfe or for the owne sake, but in respect, and for the sake of some thing else : it falleth out among those things which wee call Parerga, which are additions or adjuncts rather of ornament, then otherwise necessary.

Generall rules for Landtskip.

You shall alwayes in your Landtskip shew a faire Horizon, and expresse the heaven more or lesse either over-cast by clouds, or with a cleere skie, […].

2. If you shew the Sunne, let all the light of your trees, hilles, rockes, buildings, &c. be given thitherward : shadow also your clouds from the Sunne : and you must be very daintie in lessening your bodies by their distance, […].

If you lay your Landskip in colours, the farther you goe, the more you must lighten it with a thinne and ayerie blew, to make it seeme farre off, begining it first with a darke greene, so driving it by degrees into a blew, which the densitie of the ayre betweene our sight, and that place doth (onely imaginarily) effect.

[…].

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Of the Graces of Landtskip.

Though invention and imitation in this kinde are infinite, you must have a care to worke with a found judgement, that your worke become not ridiculous to the beholders eye, as well for true observation of the distance as absurditie of accident : that is, though your Landtship be good and true in generall, yet some particular error overslips your judgment either in mistaking or not observing the time and season of the yeere, the true shadow of your worke with the light of the Sunne, the bending of trees in winds and tempests, the naturall course of river and such like.

To settle therefore your judgement in these and the like, I whis you first to imitate the abstract or labour of every moneth. […].

If you draw your Landtskip according to your invention, you shall please very well, if you shew in the same, the faire side of some goodly Citie, haven, forrest, stately house with gardens, I ever tooke delight in those peeces that shewed to the like a country village, faire or market, Bergamascas cookerie, Morrice dancing, peasants together by the eares, and the like.

For your Parergas or needlesse graces, you may set forth the same with farme houses, water-milles, pilgrimes travelling through the woods, the ruines of Churches, Castles, &c. but you shall finde your conceipt seconded with a thousand inventions.

Drapery (so called of the French word Drap, which is cloath) principally consisteth in the true making and folding your garment, giving to every fold his proper naturall doubling and shadow ; which is great skill, and scarce attained unto by any of our countrey and ordinary Painters : insomuch that if I would make triall of a good workeman ; I would finde him quickly by the folding of a garment, or the shadowing of a gowne, sheete, or such like.

{What Method is to bee observed in drapery}. The method now to be observed in Drapery, is to draw first the outmost or extreme lines of your garment, as you will, full of narrow, and leave wide and spare places, where you thinke you shall have need of folds ; draw your greater folds alwayes first, not letting any line touch, or directly crosse another, for then shall you bring an irrecoverable confusion into your worke : […]. I would herein above all other have you to imitate Albert Durer, if you can get his peeces, if not Goltzius or some other.

Diapering is derived (as I take it of the Greeke verbe διάπερω which is, traÿcio or transeo, in English to passe or cast over, and it is nothing else but a light tracing or running over with your pen (in Damaske branches, and such like) your other worke when you have quite done (I meane folds, shadowing and all) it chiefely serveth to counterfeit cloath of Gold, Silver, Damaskbrancht, Velvet, Chamlet, &c. with what branch, and in what fashion you list.

{Of lamenesse.} The first absurdity is of proportion naturall, commonly called lamenesse, that is, when any part or member is disproportionable to the whole body, or seemeth through the ignorance of the Painter, to bee wrestled from his naturall place and motion […] : and it is ordinary in countrey houses to see horsemen painted, and the rider a great deale bigger then his horse. [...] {2. Of local distance}. The second [ndr : erreur fréquemment commise par le peintre] is of Landtskip, or Locall distance, as I have seene painted a Church, and some halfe a mile beyond it the vicaredge ; yet the Vicars chimney drawne bigger then the steeple by a third part, which being lesse of it selfe, ought also to be much more abated by the distance. [...] {4. In expressing the passion or disposition of the mind, Qualis equos Threissa fatigat Harpalice. Æneid I.} The fourth [ndr : erreur fréquemment commise par le peintre] is in expressing passion or the disposition of the mind, as to draw Mars like a young Hippolytus with an effeminate countenance, Venus like an Amazon, or that same hotspurd Harpalice in Virgil, this proceedeth of a sencelesse and overcold judgement. [...] {5. Of Drapery.} The fifth [ndr : erreur fréquemment commise par le peintre] is of Drapery or attire, in not observing a decorum in garments proper to every severall condition and calling, as not giving to a King his Robes of estate, with their proper furres and linings : to religious persons an habite fitting with humility and contempt of the world ; a notable example of this kind I found in a Gentlemans hall, which was King Salomon sitting in his throne with a deepe lac’d Gentlewomans Ruffe, and a Rebatoe about his necke, upon his head a blacke Velvet cap with a white feather ; the Queene of Sheba kneeling before him in a loose bodied gowne, and a Frenchhood. […].

{2. Of local distance}. The second [ndr : erreur fréquemment commise par le peintre] is of Landtskip, or Locall distance, as I have seene painted a Church, and some halfe a mile beyond it the vicaredge ; yet the Vicars chimney drawne bigger then the steeple by a third part, which being lesse of it selfe, ought also to be much more abated by the distance.

{4. In expressing the passion or disposition of the mind, Qualis equos Threissa fatigat Harpalice. Æneid I.} The fourth [ndr : erreur fréquemment commise par le peintre] is in expressing passion or the disposition of the mind, as to draw Mars like a young Hippolytus with an effeminate countenance, Venus like an Amazon, or that same hotspurd Harpalice in Virgil, this proceedeth of a sencelesse and overcold judgement.

{5. Of Drapery.} The fifth [ndr : erreur fréquemment commise par le peintre] is of Drapery or attire, in not observing a decorum in garments proper to every severall condition and calling, as not giving to a King his Robes of estate, with their proper furres and linings : to religious persons an habite fitting with humility and contempt of the world ; a notable example of this kind I found in a Gentlemans hall, which was King Salomon sitting in his throne with a deepe lac’d Gentlewomans Ruffe, and a Rebatoe about his necke, upon his head a blacke Velvet cap with a white feather ; the Queene of Sheba kneeling before him in a loose bodied gowne, and a Frenchhood. […].

Colour according to Scaliger is a qualitie compounded of the elements and the light, so farre forth as it is the light. Averrois and Avenpace, said it was actus corporis terminati ; others a bare superficies. Aristotle called it corporis extremitatem, the extremitie or outmost of a body. The object of the sight is any thing whatsoever may be visible, […].

Whether all colours be compounded of white and black or no.

Theophrastus hath long since laboured to proove blacke to be no colour at all, his reason is, because that colour is proper to none of the elements, for faith he, water, ayre and earth are white, and the fire is yellow, but rather would fetch it from white and yellow, whereto Scaliger leaving Aristotle, perhaps for singularitie sake, seemeth to give consent, who sets downe four primary or first colours, viz.

White in the dry body as the earth.

Greene in thicke and moyst as the water.

Blew in the thin and moyst as the ayre.

Yellow in the hot as the fire.

Yet not without reason, for Aristotle affirmed that blacke was the privation of white, as darknesse of light, to that whom Scaliger replyes nothing can be made of privation and habit, but we will leave their argument.

Whether all colours be compounded of white and black or no.

Theophrastus hath long since laboured to proove blacke to be no colour at all, his reason is, because that colour is proper to none of the elements, for faith he, water, ayre and earth are white, and the fire is yellow, but rather would fetch it from white and yellow, whereto Scaliger leaving Aristotle, perhaps for singularitie sake, seemeth to give consent, who sets downe four primary or first colours, viz.

White in the dry body as the earth.

Greene in thicke and moyst as the water.

Blew in the thin and moyst as the ayre.

Yellow in the hot as the fire.

Yet not without reason, for Aristotle affirmed that blacke was the privation of white, as darknesse of light, to that whom Scaliger replyes nothing can be made of privation and habit, but we will leave their argument.

Chap. XXI, Of the severall Gummes that are used in grinding of water colours.

Gumme Arabicke.

The first and principal is Gumme Arabicke, choose it by the whitenesse, cleerenesse, and the brittlenesse of it being broken betweene your teenth ; […].

2. Gumme Hedera, […]

3. Gumme lake. […].

4. Gumme Armoniacke. […].

Blacke is so called from the Saxon word black, in French Noir, in Italian Nero, in Spanish Negro, from the Latine Niger, and from the Greeke, νεκρός, which signifieth Dead, because all dead and corrupted things are properly of this colour, the reason why they are so, Aristotle plainly sheweth where he saith τὸ δὲ μελαν χρῶμα συνακολουθεῖ τοῖς στοιχείοις εἰς ἄλληλα μεταβάλλουσι, which is, blacknesse doth accompany the elements, confounded or commixed one with another, as for example, of ayre and water mixed together, and consumed with fire is made a blacke colour, […] : these be the blacks which you most commonly use in painting, this colour is simple of it selfe.

Harts Horne burned.

Ordinary Lampe blacke.

Date stones burned.

Ivory burned.

Manchet or white bread burned.

The blacke of Walnut shels.

Of White.

This word white in English commenth from the low Dutch word wit, in high Dutch Weif, which is derived from Wasser, that is, water which by nature is white, yea thickned or condensate, […] : in Italian it is called Bianco, in French Blanc, if we may beleeve Scaliger, from the Greeke βλάξ, which as hee takes it, signifies faint or weake : wherein happily he agreeth with Theophrastus who affirmeth omnia candida esse imbecilliora, that all white things are faint and weake, hence I beleeve it is called in Latine Candidus, from the Greeke χαίνω because whitenesse confoundeth or dazeleth the sight as wee finde when we ride forth in a snow in Winter. Il is called also albus of that old Greeke word λφος the same, […] : the principal whites in painting and limning are these. viz.

Ceruse.

White Lead.

Spanish White.

the principal whites in painting and limning are these. viz.

Ceruse.

White Lead.

Spanish White. [...] Spanish White.

There is another white called Spanish white, which you may make your selfe in this manner, […] : it is the best white of all others to lace or garnish, being ground with a weake gumme water.

the principal whites in painting and limning are these. viz.

Ceruse.

White Lead.

Spanish White.

Of whites and their tempering. Venice Ceruse.

Your principall white is Ceruse, called in Latine Cerussa, by the Italian Biacea. Vitruvius teacheth the making of it, […] ; it hath been much used (as is it also now adaies) by women in painting their faces, […].

White Lead.

White Lead is in a manner the same that Ceruse is, save that the Ceruse is refined and made more pure, […].

Of Yellow.

Yellow is so called from the Italian word Giallo, which signifieth the same ; Giallo hath his Etymology from Geel the high Dutch, which signifieth lucere, to shine, and also hence commeth Gelt, and our English word Gold, in French Jaulne, in Spanish Ialdo, or Amarillo, in Latine Flavus, luteus, of lutum, in Greeke ξανθὸς so that blacke, white, and yellow according to Aristotle are the foure primary or principall colours as immediately proceeding from the elements, and from those all other colours have their beginning.

Your principall yellow be these.

Orpiment.

Masticot.

Saffron.

Pinke Yellow.

Oker de Luce.

Umber.

Your principall yellow be these.

Orpiment.

Masticot.

Saffron.

Pinke Yellow.

Oker de Luce.

Umber. [...] Oker de Luke.

[…] it maketh a passing haire colour, and is a naturall shadow for gold.

Your principall yellow be these.

Orpiment.

Masticot.

Saffron.

Pinke Yellow.

Oker de Luce.

Umber.

Orpiment.

Orpiment called in Latine Arsenicum, or Auripigmentum, (because being broken, it resembleth Gold for shining and colour) is best ground with a stiffe water of Gumme Lake, and with nothing else : because it is the best colour of it selfe, it will lie upon no greene : for all greenes, white lead, red lead, and Ceruse staine it : wherefore you must deepen your colours so, that the Orpiment may be the highest, in which manner it may agree with all colours […].

Of Greene

Our English word Greene is fetcht from the high Dutch Grun, in the Belgick Groen, in French it is called Coleur verde, in Italian and Spanish Verde, from the Latine Viridis […] in Greeke χλωρὸν, that is, grasse or the greene herbe, which is of this colour […] : the greene we commonly use are these :

Greene Bice.

Vert-greece.

Verditure.

Sapgreene.

Of the blew and yellow, proceedeth the greene.

: the greene we commonly use are these :

Greene Bice.

Vert-greece.

Verditure.

Sapgreene.

Of the blew and yellow, proceedeth the greene.

[…].

Greene Bice.

[…].

Vert-greece.

Vert-greece is nothing else but the rust of Brasse, which in time being consumed and eaten with Tallow, turneth into greene, as you may see many times upon foule Candlestickes that have not beene often made cleane, wherefore it hath the name in Latine Aerugo, in French Vert de gris, or the hoary greene […].

Verditure.

[…], it is the faintest and palest greene that is, but it is good to velvet upon blacke in any manner of drapery.

Sap greene.

[…].

the greene we commonly use are these :

Greene Bice.

Vert-greece.

Verditure.

Sapgreene.

Of the blew and yellow, proceedeth the greene.

[…].

Greene Bice.

[…].

Vert-greece.

Vert-greece is nothing else but the rust of Brasse, which in time being consumed and eaten with Tallow, turneth into greene, as you may see many times upon foule Candlestickes that have not beene often made cleane, wherefore it hath the name in Latine Aerugo, in French Vert de gris, or the hoary greene […].

Verditure.

[…], it is the faintest and palest greene that is, but it is good to velvet upon blacke in any manner of drapery.

Sap greene.

[…].

Of Blew.

Blew hath his Etymon from the hye Dutch, Blaw, from whence he calleth Himmel-blaw, that which we call skye colour or heavens-blew, in Spanish it is called Blao or Azul, in Italian Azurro, in French Azur of Lazur an Arabian word, which is the name of a stone, whereof it is made, called in Greeke κυάνεος and in Latine Cyaneus a stone, […].

The principal blewes with us in use are,

Blew Bice.

Smalt.

Litmouse blew.

Inde Baudias.

Florey blew.

Korck or Orchall.

The principal blewes with us in use are,

Blew Bice.

Smalt.

Litmouse blew.

Inde Baudias.

Florey blew.

Korck or Orchall.

Blew Bice.

Take fine Bice and grinde it upon a cleane stone, […].

Litmose blew.

Take fine Litmose, and grinde it with Ceruse, […].

Indebaudias.

Take Indebaudias and grinde it with the water of Litmose, […].

Florey Blew.

Take Florey Blew, and grinde it with a little fine Roset, […].

Korke or Orchall.

Take fine Orchall and grinde it with unflekt lime […].

Of Red.

Red, from the old Saxon Rud, […] in high Dutch it is called Rot, in low Dutch Root, without doubt from the Greeke ἔρυθρος, which is the same, in French Rouge, in Italian Rubro, from the Latine Ruber […], from the rinds or seeds (as Scaliger saith) of a Pomegranate, which are of this colour. In Spanish it is called Vermeio, of Minium which is Vermilion.

The sorts of Red are these.

Vermilion.

Synaper lake.

Synaper tops.

Red Lead.

Roset.

Turnsoile.

Browne of Spaine.

Bole Armoniack.

The sorts of Red are these.

Vermilion.

Synaper lake.

Synaper tops.

Red Lead.

Roset.

Turnsoile.

Browne of Spaine.

Bole Armoniack.

Of Vermilion.

Your fairest and most principall Red is Vermilion, called in Latine Minium, it is a poyson, and found where great store of quicksilver is […].

Sinaper Lake.

Sinaper (in Latine called Cinnabaris,) it hath the name Lake of Lacca, a red Berry, whereof it is made growing in China and those places in the East Indies, as Master Gerrard shewed me out of this herball, maketh a deepe and beautifull red, or rather purple, almost like unto a red Rose […].

Sinaper Tops.

Grinde your Tops after the same manner you doe your lake, they are both of one nature.

Red Lead.

Red Lead, in Latine is called Syricum, it was wont to bee made of Ceruse burnt […].

Turnesoile.

Turnesoile is made of old linnen rags died, you shall use it after this manner […].

Roset.

You shall grinde your Roset with Brasill water, […].

Browne of Spaine.

Grind your Browne of Spaine with Brasill water, […].

Bole Armoniacke.

Bole Armoniacke is but a faint colour, the chiefest use of it, is, as I have said, in making a size for burnisht gold.

Of composed colours, Scarlet colour. [...] A bright Murrey. [...] A Glassie Gray. [...] A Browne. [...] A Bay colour. [...] A deepe Purple. [...] Ash colour or gray. [...] A fiery or bright Purple. [...] A grassy or yellowish Greene. [...] A Saffron colour. [...] A Flame colour. [...] A Violet colour. [...] A Lead colour.

Of composed colours, Scarlet colour.

In French coleur d’escarlite. Italicè, color Scarlatino ô porposino. Hisp. color de grana. Belgicè Kermesin of Scharlacken root. […] Latine Coccineus colour. Græc. κοκκινος of κοκκος, the seed of Kernell of a Pomegranate. The Arabians call this colour Chermeb, from whence commeth our Crimson, as Scaliger saith, two parts of Vermelion, and one of lake make a perfect Scarlet.

A bright Murrey.

In Latine Murrhinus color, Græc. μυῤῥινον, is a wonderfull beautifull colour, composed of purple and white, resembling the colour of a precious stone of that name, which besides the faire colour yeeldeth a marvellous odoriferous and sweet smell ; it is found in the Easterne parts of the world, the best among the Parthians, being all over spotted with Rosie coloured, and milke white spots yeelding a glosse like changeable silke of this colour : […].

Some have mistaken and thought that colour which wee call Murinus colour to bee this murrey which is properly the colour of a mouse or as some will have it an asse colour. […].

A Glassie Gray.

The word Glasse is selfe commeth from the Belgick and high Dutch : Glasse from the verbe Glansen which signifieth amongst them to shine, from the Greeke […] the same, or perhaps for glacies in the Latine, which Ice, whose colour it resembleth, in French it is called Coleur de voir, in Italian vitreo color di vetro, in high Dutch Glasgrum, in Spanish Color vidrial, in Greeke ὑάλινον of ὑαλος, that is moist, and that from pluere, to raine, from whence also proceed those words in Latine, humus, udus, &c. It is an ayery and greenish white, it serveth to imitate at sometime the skie-glasses of all sorts, fountaines and the like […].

A Browne.

Browne is called in high Dutch Braun of the Netherlands Bruyn, in Frence Coleur brune, in Italian Bruno, in Greeke ὄρφνινονἢαἰθοψ from colour of the Æthiopians, […] and indeed it is taken properly for that duskie rednesse that appeareth in the morning either before the Sun-rising, or after the same set.

A Bay colour.

In Latine it is called Baius aut castaneus color, A Bay or a Chestnut color, of all others it is most to bee commended in Horses, it commeth from the Greeke Βαιων which is a flip of the Date tree pulled off with the fruit, which is of this colour, in French Bay, Baiard, in Italian Baio, in high Dutch Kestenbraune taht is Chesnut Browne, it is also called of some Phænicus colour from Dates, which the Grecians call φοὶνικας but as I take it improperly, for colour Phæniceus, is either the colour of bright Purple, or of the rednesse of a Summer morning according to Aristotle […].

A deepe Purple.

From the Dutch Purple, in French Purpurin, in Italian Porporeo, in the Spanish and Portugall Purpureo, in Latine Purpureus, in Greeke πορφύρεος from πόρφυρα a kinde of shelfish that yeeldeth a liquor of this colour, […] Plato taketh ἄλος to be of a deepe red mixed with blacke and some white, and so it is taken also of Aristotle and Lucian, […].

Ash colour or gray.

In Latine color Cinerius, in French Coleur cendree, ou grise, Italian Griso beretino, Germane Aschen-frab, Hispan. color de cenizas, In Greeke τεφρώδης […].

A fiery or bright Purple.

A fiery or bright Purple is called in Latine Puniceus colour, in Frence Purpurni relnissante, Ital. Rosso di Phœnice, in Greecke φοινίκεος […].

A grassy or yellowish Greene.

In high Dutch Grassgrum, in Belgick Gersgroen, […]. Italice verde de giallo. Hispanice verde qui tiene pocode Rurio, in Latine prassinus, in Greeke πράσινον of πρασόν which is Leeke, whose colour it resembleth, there is also a precious stone called prasites of the same colour. This colour is made grinding Ceruse with Pinke, or adding a little Verditure with the juyce of Rue or herbe Grace.

A Saffron colour.

Germanicè Saffran-gerb ; Belg. Saffran-geel, Gall. Jaulne, come Saffran. Italicè croceo, color di Saffrano, […], Latinè Croceus colour, Græcè κροκινον à κροκος that is Saffron, the Etymon of that name is, […] from flourishing in the cold, for in frost and snow the Saffron flower, sheweth the fairest, and thriveth best, the colour in washing is made of Saffron it selfe by steeping it.

A Flame colour.

In high Dutch it is called Sewert-ro as you would say in English fire red, in the Belgicke or low Dutch vier-root, glinsterich root, in French Rouge come feu, resplendissante, In Italian color di fuoco, Hispan. color de fuego, Latinè rutilus aut igneus. in Greeke πύρωδες […].

A Violet colour.

In French coleur Violette, Ital. Violato color di viola, Hisp. color de violetas, […], Latin. Violaceus, à viola, which is a Violet so called of vitula, as some imagine, in Greeke ἰοειδές, ἴανθινον from ἴον, a Violet ; it hath the Etymon from Io the virgin transformed into a bullocke, who grazed as the Poets fayne upon no other berbes then Violets, Roses, Ceruse, and Litmose of equall parts.

A Lead colour.

In the Belgicke Loot-verbe, Gallice coleur de plomb. Ital. color piombo, color livide, Hispan, color catdenno, O color de plomo […], Latinè lividus of livor, which is taken for envy, because this colour is most of all ascribed to envious persons, […].